[Editor’s note: Community member Jonathan Chang (Changston on the site!) visited the recent opening of the Smithsonian’s new exhibit: The Art of Video Games. Here is his great write-up on the experience. -Chad]

Games as art. It’s one of those sayings that gets tossed around so much that it’s lost its meaning, like truly immersive experience or one-to-one motion controls. Sure, there’s stuff out there that can breathe some life into the cliché, but more often than not, reading that phrase is more likely to make your eyeballs roll into the back of your head than focus them forward in rapt attention.

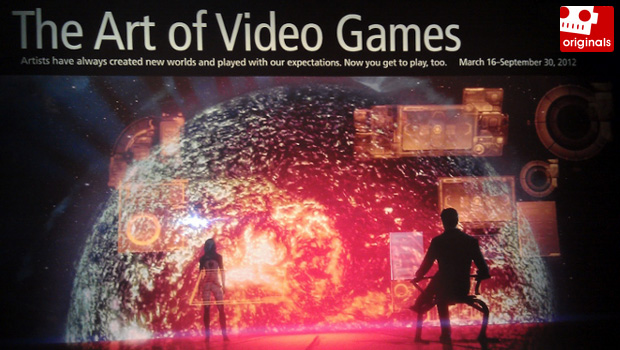

However, on March 16, those three words rang true in Washington, DC, as the American Art Museum of the Smithsonian Institute unveiled “The Art of Video Games,” the first museum exhibit dedicated to treating video games as an art form. The debut kicked off with GameFest!, a weekend-long affair including panel discussions, distinguished guest speakers, and musical performances. I may have only been able to attend on Friday, but that day alone satisfied my videogame cravings.

The opening room is the most traditional part of the exhibit, containing character sketches and stage designs of some of gaming’s most prominent characters and settings. Jim Sterling can find solace in knowing that vintage Sonic is well represented among the artwork.

Also included in this room is one of my favorite parts of the exhibit: a three-panel video display that rotates through clips of different types of people playing all types of games. You never actually see the games themselves, but you can sometimes guess what they’re playing by how they move and react to the TV. Each person’s idiosyncrasies are captivating to watch, whether it’s a kid actively moving back and forth along with the controller, or a teenager suddenly shifting from an idle haze to a state of keen alertness.

Moving on, you enter the interactive portion of the exhibit. Five different systems, each from a different era of video game history, are connected to their own projectors. This section is geared mostly towards gaming newcomers, as it includes titles that many gamers have stashed somewhere in their library: Pac-Man, Super Mario Bros., The Secret of Monkey Island, Myst, and Flower.

Seasoned veterans won’t get much enjoyment beyond the novelty of playing any of these games on a big screen, but they’ll probably smile to themselves when they see an eight-year-old kid eat his first 8-bit mushroom or yell in frustration that it was totally the arcade stick’s fault he got killed by Blinky.

The exhibit’s last room is the star of the show: a comprehensive look at videogames dating back to the Atari 2600 and Colecovision. Hundreds of thousands of fans cast millions of votes to select the 80 games on display. Accompanying every entry is a brief narration explaining the game’s historical context, as well as how it contributed toward advancing the art form. Each of the 20 consoles lists four different titles belonging to one of four genres: action, target, adventure, and tactics. The exhibit aims to guide visitors in tracing the evolution of games by sticking with one of these fields and following it through the past 30-odd years.

Is this exhibit going to give you some epiphany that changes the way you look at your favorite games? Probably not, and that’s a good thing. Chris Melissinos, the exhibit’s head curator, took a creative approach to videogame taxonomy, so I’m sure there will be nitpickers who bristle at seeing Portal labeled as an action game. But that’s okay. If he aimed to try and impress those of us who have been playing games since Clinton was president (and earlier), we’d end up with an insular and indecipherable mess of an exhibit. It would alienate the majority of the museum’s visitors and run counter to the Smithsonian’s mission statement: the increase and diffusion of knowledge.

I saw a teenager and his mother standing in front of the Flower kiosk. Even though she was intimidated by the controller in her hands, she followed her son’s guidance, tilting the controller around, harnessing the wind, and gathering petals. I spoke with her a little bit after she finished playing, and she said that she was drawn to the game simply because she liked gardening. Sure, she could have followed the museum’s directions and figured out the game on her own, but her son took the time to show her how to play.

In one of Friday’s panels, Kellee Santiago from thatgamecompany (which, coincidentally, made Flower) repeatedly said that she wants videogames to foster dialog. In the museum, you see teenagers enlightening their parents as to why they “waste their time” in virtual playgrounds. You see parents sharing childhood memories with their sons and daughters, showing them that games don’t need a glossy paint job or lifelike sound to be enjoyed. That kind of mutual understanding is the best result that Santiago could ask for.