There’s a second part, too!

For almost a decade, I used to hate being an adventure game fan. It meant that I had experienced some of the best writing and most inventive gameplay the medium had to offer, only to have that taken away from me by a market that screamed, “No! We want to shoot more chaps in the groin!” The adventure genre went from being gaming’s golden child to being commercially nonviable and generally ignored. On the rare occasion when a new game appeared to remind me why I loved the genre so much in the first place, it would flop, and I’d be left trying to explain to countless people why they were insane for overlooking some truly incredible titles.

That this grim era of desperation seems to have passed us doesn’t mean the struggle is over, though. Not at all. I’ve been lucky enough to get the chance to pick the brains of four helpful gents, each who have had a significant impact on my favorite genre: Al Lowe, creator of Leisure Suit Larry; Dan Connors, CEO of Telltale Games; Dave Gilbert, creator of the Blackwell series and founder of developer/publisher Wadjet Eye Games; and Josh Nuernberger, creator of Gemini Rue. They offered their insight into the state of the adventure genre, how it has changed over the years, and what the future holds.

In the first part of this two part feature, I’ll be looking back at the history of the genre, its fall from grace and how it started its slow ascent back into the hearts of gamers.

The 80s through the mid-90s have been called the golden age of adventure gaming — it’s easy to see why this period gained such a moniker. It’s hard to think about the genre without taking note of Monkey Island, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry, or Indiana Jones, just to name a few. The adventure giants, LucasArts and Sierra Online, offered us an absurd number of challenging, witty, and frequently hilarious games as well as gripping mysteries and psychological horrors, in which we could immerse ourselves for far too many hours.

Although I’ve never been one to play a single genre exclusively, back then, I could have probably just played these games and been more than content. Dan Connors, CEO of Telltale Games — a success story I’ll be looking at in our forthcoming second half — emphasized how important these titles remain today and how dissatisfied gamers still look to them as the high points of the medium. “From a creativity standpoint, it was a golden age then of just all this young, super talented, super brilliant people who had all this time to invest in creating these amazing characters that are totally perfect for the space, like Guybrush…. [It’s] so deeply ingrained in the gaming culture and the gaming ennui.”

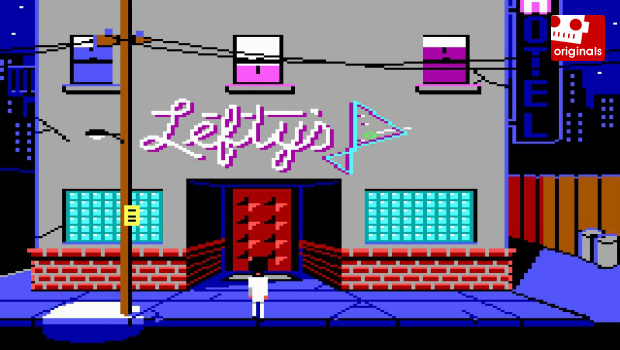

A significant portion of my youth was swallowed up due to the creations and contributions of Al Lowe. While at Sierra Online, he worked on such classics as Kings Quest and Police Quest, but he’s best known as the creator of Leisure Suit Larry, a series chronicling the misadventures of one Larry Laffer, a sleazy, horny, double entendre-loving wannabe womanizer. Adventure games were still in their infancy; it was a time of experimentation and risk taking.

“I remember going to a video store with Ken [Roberts, co-founder of Sierra Online],” Al reminisced, “We walked down the aisles and looked at all the headings above the shelves, and he said, ‘Why are there no mystery games? Why are there no western games?’ And so that was one of the things he tried to do, to get Roberta [Williams, creator of Kings Quest and Phantasmagoria and co-founder of Sierra Online] to do a mystery product and Jim [Walls, creator of Police Quest] to do a police product and me to do a western game [the hilarious Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist].” Al calls this the baseball strategy — Ken would look at what was missing from the game space and he’d try to fill it, like hitting a ball to where there are no fielders. It certainly served Sierra well, as their products filled many niches.

Most of these games were written and developed by people who had to teach themselves. There certainly were none of the classes, courses, or workshops that we have now, and there wasn’t much in the way of a previous generation to learn from, either. “You have to understand, when I started, there were no computer classes available to me. This sounds impossible to anyone growing up in the 80s, but when I started in 77, the only courses available were in COBOL and Fortran; BASIC was just a joke. I learned to program in BASIC merely by reading books, but Ken said my BASIC code wasn’t good enough and I’d have to learn assembly language, so I bought a bunch of books… I couldn’t take a class, there weren’t any.”

That meant there were a lot of design choices that would seem like shortcuts or attempts to make the game artificially longer today, but it was that trial-and-error approach that allowed them to perfect the genre. Being about the same age as the Leisure Suit Larry franchise, I’m young enough that my first foray into the series — and into adventure games in general — occurred right as the art, animation, and mechanics started to evolve into something more recognizable to the modern player. Simple sprite art was on the way out, and gorgeous hand-drawn art started to take center stage. FMV titles like Phantasmagoria and the Tex Murphy series gave players a whole new perspective to enjoy; while they didn’t age particularly well, back in the 90s, they made me feel like I was interacting with the real world and not just with a videogame.

Although the FPS genre is often cited as the catalyst for the technological leaps in gaming, adventure games advanced the medium by leaps and bounds long before then, especially in terms of how we interacted with the environments. I still have a soft spot for parsing, typing in commands, and hoping for the best, or at the very least, discovering an Easter egg or hidden joke. But that was eventually dropped for more convenient interfaces which involved more clicking and a lot less typing.

That’s not to say that gamers didn’t develop a case of rose-tinted glasses. Even back then, people wanted to return to the old ways. In Larry 7, parsing was actually included as an alternative feature, but it never took off. “The problem was,” Al explained, “in Larry 7, people tried it once or twice and thought it was cool, then ignored it. It just proved to me that whatever group of people said to bring back parsers were wrong. They didn’t really want to do that, they were just enamored with the concept.”

Unfortunately, during the mid to late 90s, adventure games started to lose popularity. Even the big titles weren’t bringing in many players. The future looked bleak for Sierra, as Al reminded me, “When 3D graphics cards came out, it looked like the future of gaming was going 3D. With the rise of the shooter genre, the money and interest had to come from somewhere, and it really came from adventure games. Plus, a lot of the games stole a lot of the ideas that made adventure games work, like inventories, puzzles, and conversation trees, and those became integrated into those other games.”

What I found most surprising about the way other titles adapted adventure mechanics into their gameplay was how so many people completely forgot where they came from. It was a sad time for fans like myself. “Larry 7 was the last adventure game that really sold well. I remember when Grim Fandango came out after Larry 7, it was at a time when LucasArts was producing these great products and everybody loved the game, the gameplay was great, but it sold like crap.”

Grim Fandango‘s failure was something of a tragedy, really. Such an immensely clever game, with memorable characters, a wonderfully told story, and a unique art direction, deserved to succeed. While the critics and those who actually played it loved it, it went by generally unnoticed by everyone else. It is somewhat fitting, however, that this tale of a Grim Reaper would herald what many felt was the death of the pointing and clicking. The focus shifted from stories and puzzles to action and graphical fidelity.

“Suddenly, these games where you’d sit and pound your head and try to figure out what to do next looked antiquated and old and slow. But the more I played the new games, the less I liked them and the more I appreciated puzzle solving. And also, I really liked humor — I love Monkey Island and Space Quest and those games that made you laugh, where there was a big pay off and a belly laugh coming in. Man, that just went away completely. There were no products that had any sense of humor back then.” Al’s love of humor in videogames is something we share, perhaps because it is so rare. A game that makes me actually laugh is something I cherish, even if it’s just because of some terrible puns or a bit of slapstick.

That’s not to say there weren’t any developers trying to bring humor back into our wonderful hobby. Seven years after Grim Fandango felt the sting of an apathetic market, the game’s designer and LucasArts alumnus, Tim Schafer, gave gamers the gift of Psychonauts, a unique experience that merged action and platforming with the storytelling and puzzles of the adventure genre. People still talk about it today, but it’s just a shame that few people were doing so in 2005.

Psychonauts‘ combination of styles is something that I think fits adventures very well. Story and puzzles are at their core, and there’s no reason why players cannot experience those things through action and platforming or even driving and shooting. It was this sort of thinking that almost brought us the action/comedy Sam Suede. Al Lowe formed a new team to create a console experience which attempted to combine 3D gameplay and action with the comedy and narrative of golden age adventures, but it was never finished.

It’s clear that Sam Suede is still a sore topic for Al. “Psychonauts came out and sold 50,000 copies or whatever and went immediately to the bargain bins. It was like every publisher looked at our stuff and said, ‘Well, what are your comparables?’ We said there really aren’t any comparables because we’ve got sexy girls, a lot of funny conversation, and they said, ‘Well it’s an action comedy and the only action comedy we know is Psychonauts, how did that sell?’ Oh shit. So we evidently got tarred with the Psychonauts brush and we just could not find a publisher who would take a risk.”

Even when the developers tried to bring gamers back into the adventure fold, publishers lacked confidence in the genre. It would be easy to just pin all the blame on the publishers — after all, we do that a lot with other things. But when their biggest concern is the bottom line, if they don’t see anyone buying these types of products, then there’s no reason for them to take these massive risks.

By the second half of the 2000s, things were changing. After LucasArts cancelled the long-awaited sequel to 1993’s Sam & Max Hit the Road, a group of designers left to form their own studio, known today as Telltale Games. Their first titles were Telltale Texas Hold’em, a couple of episodes based on the Bone comics, and a series of CSI spin-offs. After securing a round of investments, they were eventually able to work on adventure IPs like Sam & Max and Monkey Island, something old adventure game fans like myself had been waiting on for a very long time. CEO Dan Connors believes that this had a large influence on bringing the genre back into the public eye.

“Certainly, the adventure genre seems to have grown, as far as the size of the audience is concerned, since we started in 2004, and I believe Telltale has had a roll in that. Tales of Monkey Island and Sam & Max succeeded in capturing the essence of what was great about the original games and modernizing the experience.” Dan recalled, “I think we built games that allowed a new generation of gamers to experience franchises that were considered legendary but weren’t the type of thing the average gamer was going to dig up and play. With Back to the Future, we built a game that used adventure mechanics and was received well by a mass audience.”

By securing their own funding and taking out the publisher middleman, they were able to bring these games to a new audience despite the risk involved. Publishing these titles themselves was far from the only reason for their success, however. The rise of digital distribution and episodic content has had a massive impact. This is something I’ll be looking at in greater depth in the second part of this feature.

I hope you’ll join me, but until then, go and play some adventure games!