How will you spend your 60 minutes?

Jason Rohrer is probably a name you’ve seen mentioned at least once during your life as a video game fan, but whose work you may be unfamiliar with. He’s an auteur, a one-man-band of a developer who put out his first game more than a decade ago. I first became aware of the man when Alt-Play: Jason Rohrer Anthology was ported to DSiWare. Included in the pack is perhaps his most well-known game Passage, a critical darling and one of those art games some would turn a nose to for valuing a message over mechanics.

That’s how I looked at both Passage and Gravitation the first time I played them.

“Ugh,” ignorant CJ thought “I get it, you work too much and life is full of difficult choices. Get over yourself.”

It’s easy to dismiss any game with a concrete point-of-view as self-involved, especially if, like me in those years, I thought of gaming as merely a vehicle for delivering entertainment rather than something that makes me keenly aware of my own mortality. And yet, I return to both games on an annual basis. As time passes and my own life continues to be unfulfilled — fuck me, I turn 33 this year — the message of both games actually begins to speak to me, now doing so so loudly I see my life and my choices in every pixel on the screen.

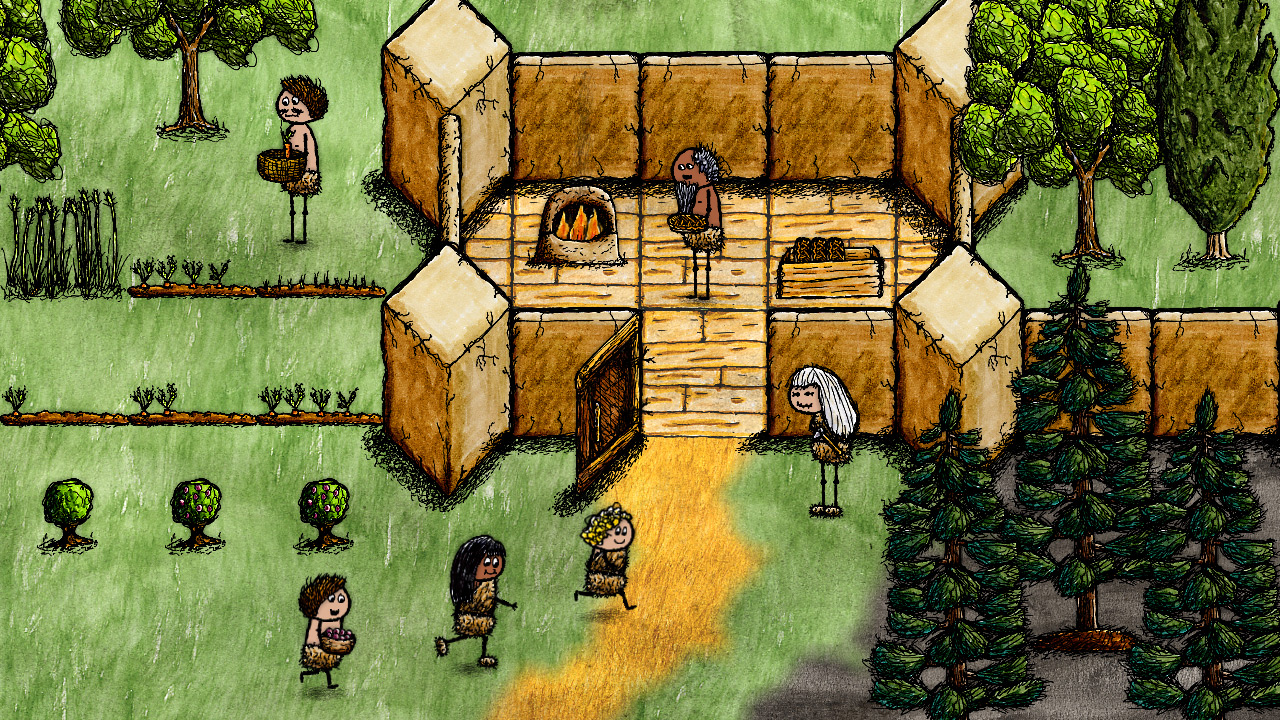

Our lives and how we choose to live them is the central theme of Rohrer’s newest game One Hour One Life. It’s set to launch later this year as a co-operative civilization building sim played at a micro level: every player starts out as a child living one year for every minute that passes, and as they grow they must decide how they will contribute to and build up a society for future generations to enjoy.

“The world in the game essentially starts off as an infinite expanse,” Rohrer explained to me at the first of two coffee houses I would visit for our Skype interview. “There’s untouched wilderness stretching in all directions and plopped down in the center of that wilderness is the first player playing as Eve. Each additional player that joins the server is born as a baby to some other player on the server. So the second player is Eve’s first child and the third player is Eve’s second and so on. As the characters grow up they’ll reach a point where they will start giving birth to new players as well.”

As the population grows and more humans are born into the world, players will have to work together to build up a society as best they can. It’s a stark contrast to what he found in a thematically similar game in Rust.

“In Rust for a while I was trying to run a hotel,” Rohrer said. “People who are traveling from another side of the map need a place to store their stuff or players who are just starting out and haven’t built a big base yet may want to rent a room in a nice strong building. So I built this hotel with all these rooms and also build a store and a restaurant as a place where people could heal up. No one ever patronized them, even though I was selling stuff in the store new players wouldn’t yet have access to. I wanted to know why. Why isn’t trade emerging here?”

It seems like a silly proposition until I recall my brief excursions into the early days of Rust. Mostly, it was my avatar walking around for about 30 minutes until another player would come along and murder me. I also once caught some dude straight up jacking my wood from my rickety shack before he murdered me. Games like Rust are exercises in objectivism: I am all that matters and I will let nothing stand in my way. It’s why it’s so easy to kill other players for supplies and perhaps why Rohrer’s little society never developed.

“I once had a guy continually cement over my door [in Rust],” he said “and that’s something that never happens in real life. Nobody has ever done that to me, even if there were angry with me. And I wondered why isn’t trolling as big a problem in the real world. And the reason why is if there were a person who cemented over my door in real life, and he did it to a bunch of other people, eventually they’d be physically detained in a way they couldn’t overcome or if they resisted apprehension they’d be killed.”

“In Rust that’s true too, if somebody annoys you enough you can just go kill them, but it doesn’t mean anything because of how respawn works. You tell someone to stop or you’ll shoot and they’ll say ‘Go ahead, I’ll just lose the gear I’m wearing and respawn in my base a mile away from here.’ So trade doesn’t happen, and because death isn’t real justice doesn’t happen and I think the reason those occur in real life is because death means something. I’ve fantasied about making a game with perma-death but I have a family to support, so I wanted to see how close we could get to making death matter.”

One Hour One Life is a bit of a mix of the two ideas. When your hour is up — or if you somehow die before then — you re-enter the world as a helpless baby once more to a completely new mother in a community on a different part of the map. Approaching open-world survival games like this, Rohrer hopes, will force players to band together and actually work towards the common goal of developing a functioning society.

“The idea of a civilization and social structures building themselves up is tantalizing to me. From a philosophical standpoint trying to figure out how to explain them, why they come about, why is the way we do things the way we do things and to build a game where people don’t have to do those things but they kind of end up doing them anyway may help us understand why we do them in real life.”

It’s not going to be an exact recreation of how our society went from arrowheads to iPhones, two images Rohrer used when he first announced the game, but it’s an admirable goal to attempt. There was no blueprint for our forefathers, no instruction guide listing the tools needed to get to where we are today. Rather, we got here with small steps and great leaps across thousands of years, something Rohrer thought about while developing the initial concept for the game.

“I gave a talk at GDC when I announced the game and thought about the roughly four thousand years it took us to get from arrowheads to iPhones. That was the original thought experiment that led to this game. Even before working on this I’ve talked about this with people to muse about. If we had to do it again from scratch, if we were naked in the wilderness with nothing but rocks and sticks, how long would it take us to get back to the iPhone. Even with all the knowledge we have today, it took us 4,000 years the first time, how long would it take the second?”

It won’t take that long here to reach our current point in history, but will players give the game enough of a chance to see the advent of Apple’s attention span destroyer. Rohrer is planning on 10,000 in-game objects to be added to One Hour One Life. This includes vehicles, machinery and more, all centered around getting our animal skin wearing ancestors to become the avocado toast eating deplorables we are today. But to get there, players will have to stick around past the first few minutes of existence. As a baby, you can’t really do anything and your survival is dependent on those around you. In those minutes, your life is in their hands. If they actually help you grow into an adult character, you may have to do the same for someone else.

“I want there to be a period of mostly helplessness and I think right now it’s three to four minutes where you’re at your parents mercy and you hope they’re going to take care of you. Your mother can pick you up and feed you or a male character can pick food to give to you, but both take away from the food supply. So as a baby you have to develop a way to let them know when you need to be picked up and not just spam them and waste a bunch of resources.”

For absolute success, it’s imperative to develop this parent-child relationship as whatever actions you take as the parent, your children will have to carry on if they want to survive. Survival becomes a family business at this point, and arguably budding societies may develop an “it takes a village” mentality to move forward.

“Imagine two different population pockets in the game. One really cares about babies, takes care of every single one as best they can, puts every resources possible into them, and the other couldn’t care less about their babies. The only source of new players to continue your civilization into the next hour is the new batch of players that arrives as babies. So those two pockets, one is just going to wither and die and become the end of civilization if they don’t take care of any babies whereas the other one is just going to continue to grow and get more and more people.”

Of course, it is still possible to care for babies and have your village die off. As this is an open-world survival game, resources are king. Overeat and it’s game over for your town. Feed the baby too much and it could have the same disastrous result. Societies that are more efficient with their supplies and keep their women healthier are more likely to have new babies born into them rather than those groups of players who struggle to progress. Beyond food, players will also have to watch how they gather resources from the world as it’s possible to ruin necessary plants from producing new supplies in the future.

“As a simple example there are these milkweed plants in the game that are used to make rope and different kinds of string. The milkweed plants go through a cycle where they’re in a leafy phase, then they flower and then they go into seedpods. They go through that cycle every couple of minutes or so. If you pick them at the wrong time to make your rope they won’t grow back. If you see a player picking them at the wrong phase you might go yell at them. So those kinds of lessons, those cultural things, explaining how the world works to the next generation, this is what I hope can be passed down.”

If done correctly, the passage of knowledge is something that could help every society. If you grow up and die in an advanced village, and then respawn as a baby in a town years behind in terms of technology, you could be the player that helps this village figure out how to grow and succeed. Taking all the knowledge you learn in one life and applying to next is how players can make their dent in society in such a short amount of time.

“These are the things that, as I’ve gotten older and reflected on my life and the generations that came before me and looking at my kids, I’ve thought about and looking at the bigger picture I wanted to make a game that is about these bigger picture issues and why things are the way they are.”

To really grasp that big picture, One Hour One Life has to be a big game. As mentioned before, Rohrer will be creating 10,000 objects in the game for players to craft along a presumably gargantuan crafting tree. What I first noticed about the game when I viewed its trailer is the vast difference in art direction compared to his previous title. One Hour One Life looks like a more family-friendly version of Don Hertzfeldt and for good reason: one person creating 10,000 objects in the game using pixels would take an exorbitant amount of time. For this, Rohrer developed a program that will recognize black lines drawn on a scanned image and allow him to create that object in a matter of minutes. And he plans to do that roughly every week for the next two years.

Add those post-release content years to the several this game has been in development and you have a project that has taken up a good portion of Jason Rohrer’s notable life. It’s humbling reading up on a man who has had his own art exhibit, made several video games by himself, crowdfunded his own DS cartridge, helped develop a local currency, and, as I found out during our talk, built his own wood fire kiln to make his own pottery he dug out of the ground. I can’t help but feel my life in comparison is one not well lived. As I look around the room I rent in the crappy house I live in, that feeling turns into a confirmation. If I were to die tomorrow nobody could look back on my three decades on this planet and say I contributed in any way. Nothing I am doing today will at all help society tomorrow, and I will be forgotten as quickly as I was conceived.

Dark stuff, I know, but it’s what Rohrer games bring out of me. The titles of his I’ve made time in my life for have a great focus on death and the choices we make in the years leading up to our demise. One Hour One Life carries on that tradition, but in a way where each player can actually make an impact in their fleeting existence.

“Obviously death has been a constant in my career either in the title or the underlying anxiety present in my games and that’s definitely present here. It kind of brings everything together from all the different things I’ve thought about in my separate games coming together in this great big cohesive whole in this game. Death and the choices we make knowing that death is inevitable are intrinsically linked. There is something about this pressure and knowing that these moments are passing and will never be repeated again and you have a limited supply of them that makes the whole thing matter and makes the choices you make along the way matter because you’re never going to get another today.”

One Hour One Life is set to launch in just a few months. Rohrer says all the bugs have been squashed and now he’s just busy adding objects to the game. As of this writing, there are just under 300 man-made objects in the game, or 3% of his self-set goal. I look forward to 2020, when Rohrer puts that last object in the game, and I hope it develops enough of a following that people who wait to jump in then can journey through a magnificent world of communities existing in different eras of human development. I hope enough people give it try to see just what greatness we can achieve if we work together as a society and not as self-interested individuals. Because we didn’t go from arrowhead to iPhone alone, we did it together, even if we didn’t often know it.

If you would like to know just how he does it and has done it for more than a decade, Jason Rohrer will be giving a speech at GDC in March as part of the Independent Games Summit.