You’re no Sidney Prescott

It’s finally cold in New York, leaves have turned a late orange, and gloomy October feels much farther than the promise of chilly, cheerful (depending on how much you like your family) December. We’re slowly fading into the next year, but although Halloween is well behind us, I find playing horror video games to have year-round pertinence. Case in point, I just started replaying Bloodborne for the millionth time. Its grey skies and black clothing feel fitting for this time of year, when the sun sets at 5 p.m. and you head home early to avoid the cold.

This will be the final column under my Terrible Females theme, and, as perhaps you have gleaned from my introduction about the enduring nature of horror, I’ve been thinking about one element of horror games that truly sticks around: women, if you can even believe it.

Horror movies have started to progress past the stereotypical Final Girl and onto a Final Girl who is more openly sexual and feminine (Cam, Midsommar, and Ready or Not are some newer examples), but the traditional Final Girl still heavily defines the genre (A Quiet Place, Till Death, and Candyman are recent examples of its enduring influence!). Horror games, however, have managed to avoid the trope for most of its history.

Going back to Bloodborne, non-playable characters like The Doll, Yharnam, Pthumerian Queen, and Arianna are all sexual or visually feminine characters, and yet are all allowed to live (depending on how you play the game) until the end. Unlike women characters in horror movies, these characters aren’t punished for their sexuality or their open expression of womanhood. They’re presented adorned with bows, in dresses, or, more grotesquely in the Pthumerian Queen and Arianna’s case, bleeding or battered from childbirth. As players, we accept this womanly presentation at face value. During a horror movie, you might spot the promiscuous, dress-wearing woman early and tell yourself she’s going to die. But womanhood in a horror game is too active for that.

That doesn’t mean, though, that horror video games never indulge themselves in the stereotypical “strong” woman character. When you scroll through photos of famous woman horror game protagonists (especially in survival games, the video game equivalent of Final Girl-heavy slasher films) you see a lot of ponytails, short hair, and generally modest clothing.

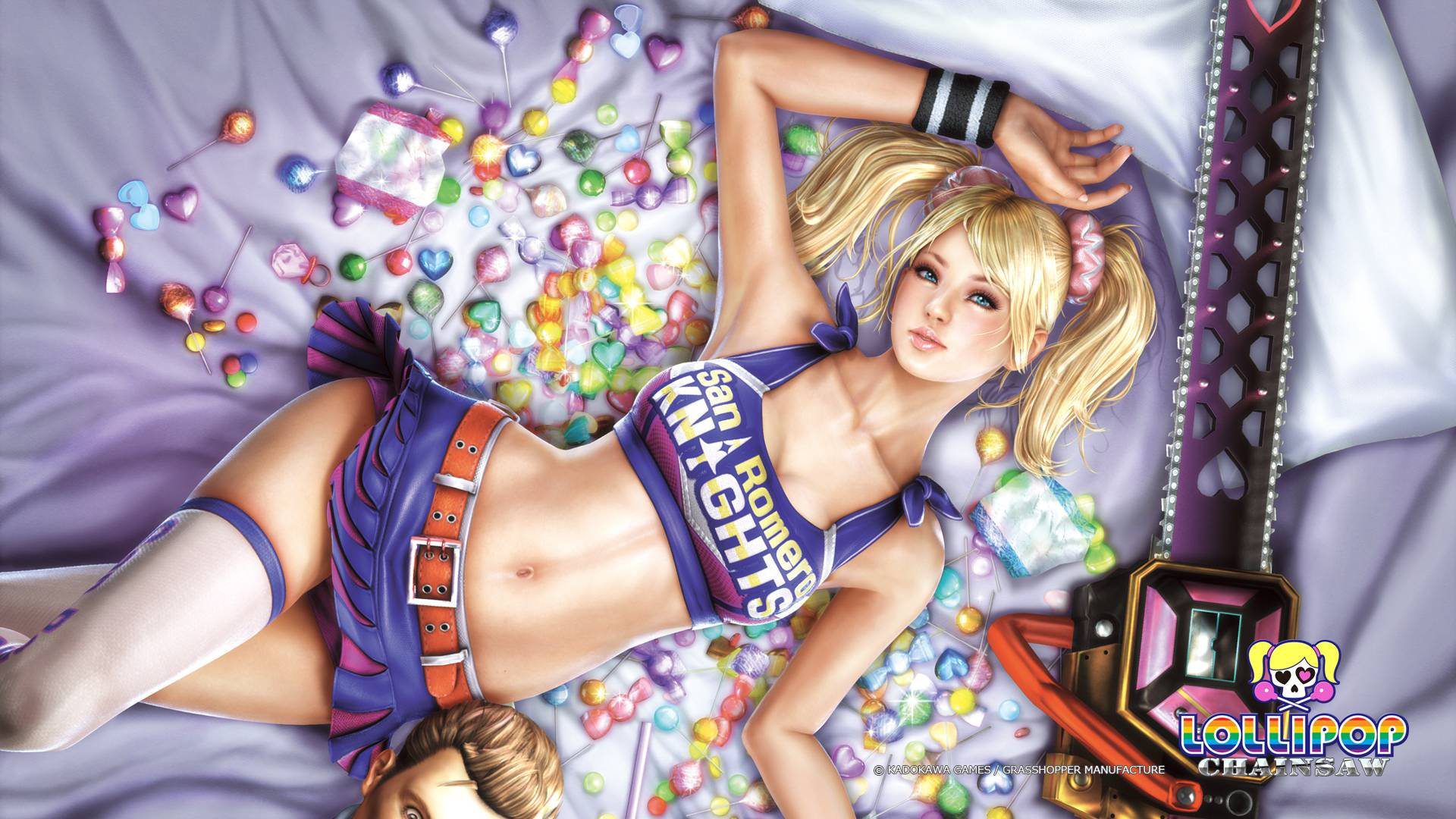

When video games do focus on a single woman character, she tends to be a subversion of the typical Final Girl. These characters, like Juliet from Lollipop Chainsaw and Aya from Parasite Eve, may be partially borne from video games’ penchant for hypersexual women. But horror movies rarely give us this kind of character outside of Jennifer’s Body, so it can be nice to see.

Personally, I think that video games’ Forever Girls exist because, unlike movies, which necessitate a passive audience, video games anticipate an active, and often even aggressive, audience. Instead of delighting in watching a killer slice open girls one by one the way a movie-goer would, a video game player is most satisfied in making their own choice — will they kill the girl themselves? Will they help her? Will they die instead?

So, video games’ Forever Girls aren’t totally immune to the same misogyny that created film’s Final Girls, and, outside of that, it would be nice to see video games diversify their female characters, especially in terms of personality, looks, and race. In any case, it’s worth noticing the way women heavily populate the horror genre, and I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on that in the comments. Nothing scarier than female domination!

[More articles in the “Terrible Females” series: Anatomy of a woman monster, Against the damsel in distress, When you’re a girl, you get used to blood.]