Throwing money at your problems won’t make them go away…but it sure feels good

In support of World Mental Health Day back in October, game developer Will O’Neill ran an offer on itch.io for a bundle of two of his visual novel/adventure games, Actual Sunlight and Little Red Lie. Both games take a bold look at mental and physical health problems and how they interact with each other, while also analysing how differing socioeconomic circumstances can affect a person’s experience of such challenges.

Both games can be quite bleak in their outlook. There are the pleasant-yet-downtrodden of society who are hit hard by every setback they experience, while hideous personalities seem to float above all of the crises they unleash. However, the games don’t reduce good and evil to how much cash the characters have in their wallets; it instead paints a picture of their different types of struggles, where they learn, and where they fail to learn.

The big message I took away from playing the two games consecutively is that having wealth is becoming increasingly vital to keeping healthy. However, being rich isn’t a solution to everything; you also need the right attitude, since money can also simply be used to paper over the cracks. Until it’s no longer there. Even if you do have endless amounts of cash, that can be squandered on quick-fix solutions, if you throw money at your problems instead of facing them, truthfully and head-on, they will never go away.

Actual Sunlight: a painful white collar existence

If you’ve experienced Will O’Neill’s games, you may be wondering how Actual Sunlight has anything to do with the interplay between money and health at all. Actually, after playing Little Red Lie, I think one of Actual Sunlight‘s core themes is the financial instability of the “millennial”, white collar worker, and how this can fuel mental health problems.

During Actual Sunlight, you play as Evan Winter, a man who struggles with dysmorphia, depression, and suicidal thoughts. You lead him through his mundane existence as some non-descript marketing/sales grunt. You see him contemplate jumping off the roof of his apartment on a regular basis, and guide him out of it. You see his stilted interactions with coworkers and strangers due to his distorted mindset. And you see his unhealthy relationship not just with food and with himself, but with money.

You can look through Evan’s bank account at an ATM (heavily in debt with no savings), and Evan is depicted as feeling guilty about spending his money on video games, crucially, because buying them seems to be a compulsive action for him. Money feeds Evan’s addictive and self-loathing behaviours, and his debt is in part a consequence of his illness. When he smashes up his apartment in a fit of self-hatred, it is an irreversible act of self-harm, since he has no money to replace things. The inability of Evan to move up in his life in any way due to his financial situation, self-imposed and due to general economic decay, hangs in the air. Money money money is all that matters in Evan’s life, at work or at home.

It’s difficult to say whether an Evan Winters character would be able to get on top of his demons if he weren’t stuck in the cycle that a lot of people in their late twenties/early thirties experience: not only the inability to save up funds and to hit milestones but entering into an unhealthy relationship with money. Because of his compulsive ways, extra funds would fly through his fingers. Yet he does not have the confidence of an Arthur Fox (see below), so the money will eventually run dry. Unless the extra money would fix his shattered confidence? Unlikely; money as an emotional crutch is always just a temporary solution, as is depicted in Little Red Lie.

Little Red Lie: the Stone family

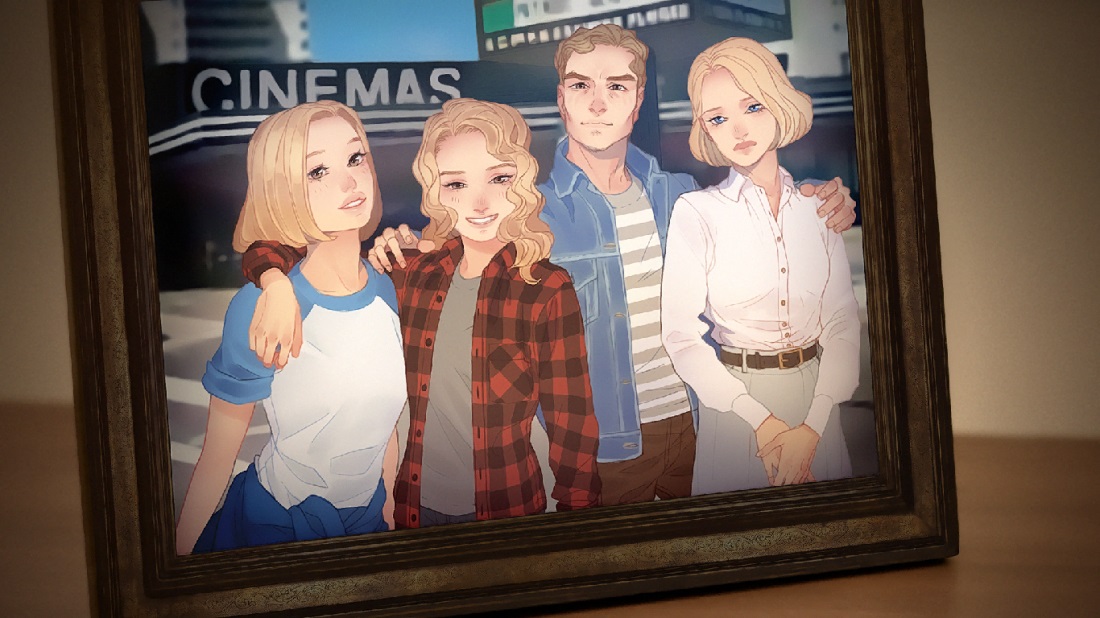

Little Red Lie tells the story of two separate characters: Sarah Stone (and her family), and Arthur Fox (and everyone in his blast radius). It’s a stark contrast, since the Stone family were once well-off but have depleted all their reserves, while Arthur can’t spend money fast enough. How their situations affect, and are affected by, their differing bank balances is at the centre of the entire game.

The Stone family have been hit by multiple crises in recent years. Mum has multiple sclerosis and needs extra help, while the sister, Melissa, attempted suicide a few years ago and has since refused to leave her basement bedroom. Both are on an extensive list of medications, which gets the family into financial difficulties. The core character, Sarah, has been hiding the fact she has lost her job, while the dad, an ex-police officer, has to balance putting on a brave face for his wife and facing off with the bank manager. From the beginning, there is a sense that the family is in denial that bankruptcy is imminent, and the family later get into some shady arrangements to get by.

The complexity in Little Red Lie is that it does not only show those in obvious poverty struggling to fund treatment for their health problems. The Stone family once firmly belonged in the ranks of the middle classes, have a huge house, and are accustomed to a certain way of life. This is what makes their slide into true poverty, when their home is being repossessed and they end up cutting down on all but the necessities, so much harder for them to accept.

Later on in the game, Sarah encounters a family who knows abject poverty, not just relative poverty. When a member of that family commits a crime against Sarah, she is expected to be understanding because of this difference, even though Sarah has still lost everything. For me, this emphasised that being unable to pay your medical bills and the consequences of this is the same experience, whether you’re being evicted from a Victorian townhouse or sharing a run-down house with four other families. And either experience can drive you to desperation. Having a taste of privilege before this poverty, though, can be maddening.

Ultimately, Sarah’s pride about being a “rich poor person” leads to her downfall. By struggling against the fact that she no longer has a comfortable lifestyle, she puts herself in dangerous situations. Does she really do this to make life better for her family? Or because she cannot bear her family being less than upstanding? As we see from the interactions with their bank manager and nurses at the public hospital, it doesn’t matter how the Stone family wants to be perceived or treated, or how they imagine themselves to be – once the money dries up, nobody will help.

Little Red Lie: Arthur Fox

Unlike the Stones, Arthur Fox is a whirlwind of money. A motivational speaker with sociopathic tendencies (think a chubbier, older Patrick Bateman, as clichéd as that is), Arthur admits he thinks money is the only thing that matters. He throws hissy fits if he has to fly economy class, he wastes money on prostitutes and drugs, bullies his way into getting a limited edition “sex car” and then crashes it into the side of a strip club. Money represents power for Arthur, and he needs to show off this power to reinforce it.

Money gives Arthur more room to fuel his narcissism and his addictions. You also get the sense that his superficial charm and the way he radiates control makes him irreplaceable at his job; he gets rehired at his old job, despite critically injuring a bouncer and raping his assistant. When Arthur’s health insurance gets declined, he throws a ream of credit cards at the administrator of the private hospital he’s staying at after crashing his car; he doesn’t panic at having his insurance cut off, because he doesn’t know how it feels to lack money. It simply cannot happen to him – until it does. Even then, he has to go on a suicidal jaunt to Las Vegas (partying with sex workers and heaps of crack before planning to shoot himself in the head) before the money really dries up. Then circumstances align to save him once again.

Being rich seems to save Arthur from self-imploding, but in truth, it means he never has to change. He can always throw money at his problems, and ultimately that’s what Arthur does. After his final breakdown, all he does is spoil his children to show his love, buy his neglected wife a bunch of plastic surgery, and visit life-coaches. Fox never takes responsibility for the lives he’s damaged, or shows any type of guilt. Narcissists never see the error of their ways, regardless of how much money they have, but their narcissistic acts never cause difficulties for them, so long as these acts never leave them in financial need. Arthur will probably live a long life, unlike the Stones, but he will never live an authentic life, and he will ignore his problems to the end.

Enjoying sadness

Overall, Actual Sunlight and Little Red Lie are great games to play, though you should prepare yourself in advance for how emotionally touching and draining they can be. Actual Sunlight is a little on the short side, but Little Red Lie showcases just how far O’Neill has come in building on the themes of mental health, what it means to be poor and how society neglects those in need. In times when the right to universal healthcare is increasingly called into question, not just in the US but in my home country of the UK as well, it’s an important reminder as to the damage that can be done by making healthcare a business, thus linking health even more intrinsically with money.

Have you played Actual Sunlight or Little Red Lie? If so, what did you think? Have you played any other games that deal with similar themes? Let me know in the comments down below.