Think back: what’s the most awful game you’ve ever played? Regardless of when exactly you leapt headlong into gaming, chances are that your answer will be based on some movie or television license — or music, if you were ever unfortunate enough to encounter Revolution X. Licensed games have historically sucked, and not in that “oh, it’s kinda flawed” sort of way; games based on preexisting properties have been eternally hexed to suck — the track record, as you’re no doubt already aware, seems proof enough.

I have a theory: somewhere in Acclaim’s basement is an infernal contraption, a devil’s machine, which one can use to convert an existing intellectual property into cash money. The mechanics behind this machine are unknown to all who behold it, a great and terrifying black box — instead, all we can do is look at what products the machine pumped out and try to reverse-engineer the processes by which these horrible, horrible things came to be. To this end, I endured a full day of awful circa 1988-1992 licensed games, picked them down to their barest essentials, just to report my findings to you. Because sure, not all licensed games are tripe, but most of ’em certainly are.

Abandon all hope, Dtoid faithful, and hit the jump to learn the secrets behind gaming history’s worst licensed games.

So, you’re a game developer who has recently acquired a license to a hot movie, cartoon, breakfast cereal, or courtroom drama property. First, congratulations! You’ll be happy to note that most of the hard work has been done for you — thanks to the magic of Branding™, your audience comes pre-assembled and your title is guaranteed to at least make back as much money as you’ve funneled into your project.

To get the most out of your $8,000 budget, I’ve compiled a list of some helpful rules-of-thumb on making your licensed game soar. Not to say you need them or anything — I’m sure this’ll be the finest Barbie title to grace the plates of 8-year-old girls everywhere — but we take care of our own in the licensed games racket. Stick close to these Three Cardinal Rules of License Development and you can do no wrong. Happy hunting!

Rule #1: Use everything you can possibly conceive of to slaughter the player.

Making a game too easy is just asking for a customer to try and return your game, so be sure to work in plenty of deathtraps and dangerous objects careening around the stage to ensure incalculable odds of survival. If the licensed property’s universe doesn’t provide a suitable environment to torment your player, just improvise. Anything can be dangerous if it flies through the air at high enough speeds, after all.

Once you get over your fear of the limitations of the physical realm, the possibilities are endless: fire hydrants that grow arms and teeth for no apparent reason and attack; clams left on the sidewalk that deal mortal wounds just by touching you; even flying tacos that fart hydrogen bombs on the hero. Even if such a terrifying schism in reality wasn’t necessarily a part of the Law and Order television show, it’s certainly kosher to work it into Law and Order: Brisco’s Fantasy Vacation 2.

Oh, and that black thing under Dirty Harry in the picture above? It’s a Goddamn snake.

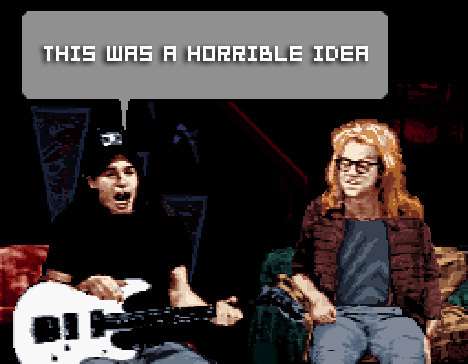

See also: Total Recall (NES) assaulted the player with a world in which every moving object not only damaged you, but also threw objects at you that damaged you. Wayne’s World (NES) was awful in every way a game can possibly be awful, but particularly for this reason.

Exception: Konami’s TMNT4 (SNES) made it very clear what could hurt you (foot soldiers, robots) and what couldn’t (pizza, sidewalks), making it an exceptionally enjoyable title that could be completed within a matter of hours. Shameful.

Rule #2: Pimping a difficult license? Think outside the box. Better yet, ignore the box entirely.

So you’ve just landed a big-name license, but it doesn’t really fit with the platformer genre which is hip with the kids these days, what with their Nintendos and Marios and such. Creating some sort of direct lift of the original property won’t work as a video game, especially if you’ve landed a license on An Inconvenient Truth or The Miracle Worker. What’s a developer like Ocean, Titus Games, LJN or THQ to do? Easy: make shit up.

Take a send-up like Blues Brothers on the SNES, pictured above. If you’re surprised that there was ever a Blues Brothers game, you’re probably not half as surprised as the poor saps who had to create the game. Jake and Elwood do little (if any) jumping throughout the film, and at no point are they ever prompted to collect and hurl any number of floating, spinning records. That’s not a game — are there any spike pits in the movie? No? Screw it, let’s use them anyway. The platforms too, and suspend some records in the air as well. Man, I feel better. Don’t you feel better?

This is the sort of dedication to a product that really inspires the hearts of developers everywhere — no matter how difficult the adaptation process might be, you sally forth, ignoring common sense at every step of the way. And why not add to the film canon while you do it? Sure, Marty McFly might not have had to dodge flying fish, bubbles, and weird mask-things while bounding across a deadly crevasse in Back to the Future II, but you know something? He fucking should have.

See also: Beethoven’s 2nd (SNES), a title created for the express purpose of discrediting anyone who would dare insist that a game based on a horrible movie dog looking for his puppies could possibly be fun.

Exception: ICOM’s Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective (SCD), which plays exactly the way Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s books read, and is therefore just as boring.

Rule #3: If all else fails, punish your customers. It’s their fault if they can’t enjoy your opus, anyway.

Maybe your attempts at creating a game to capitalize on a hot property have all turned up bunk. No matter how bad your product is, remember: it must ship, and it must ship on time. If your crapometer is leaning a little too deep in the red, you might as well just crank things into overdrive and get it done as quickly as possible — timing is important with a licensed game, after all. Who cares if it’s crap? It’s merchandise, people! Get crackin’!

Take a game like Bebe’s Kids (SNES), based on the movie of same name that was savagely raped by critics and public movie-goers alike. That’s a losing battle even before it starts — if nobody wants to see a crappy animated flick, what chance is there that they’d want to play a crappy game based upon it? The developers at Mandingo — seriously, that was their name — abandoned all hope of quality product and decided instead to make one of the most awful games in the history of the industry. And the only way we know this is because some of us played it, which means some of us bought it, which means some revenue was actually generated by Bebe’s Kids.

No matter how horrible your product might initially appear, take heart: the magic of merchandising and Branding™ ensure that a few thousand people will buy your horrible game if only for the name on the box. Don’t believe me? Go dig a hole or two in New Mexico and get back to me.

See Also: Jaws (NES), Total Recall (NES), Home Alone (SNES), every Ren and Stimpy game ever made (Various), Yo Noid! (NES), Nickelodeon GUTS (SNES). These games are so terrible, to even speak their names aloud invokes a cloud of locusts that explode into boiling acid as they swarm around your face. Don’t even try it.

Exceptions: There are exceptions?

Now that you too know what a truly great (awful) licensed game can be, it falls upon you to make it happen. Go get that degree in Library Science you’ve always aimed for, take up a programming job at a hole-in-the-wall mobile gaming studio, and get to coding. Who cares if you don’t know how? These games sell themselves, people!