Try not to slot this up, Omae

I said this last article, but I absolutely love Shadowrun. I look for its pulp novels every time I’m in a used book store, and I read the sourcebooks, even though I don’t have any tabletop friends. I’m just in love with its world, its marriage of cyberpunk and high fantasy.

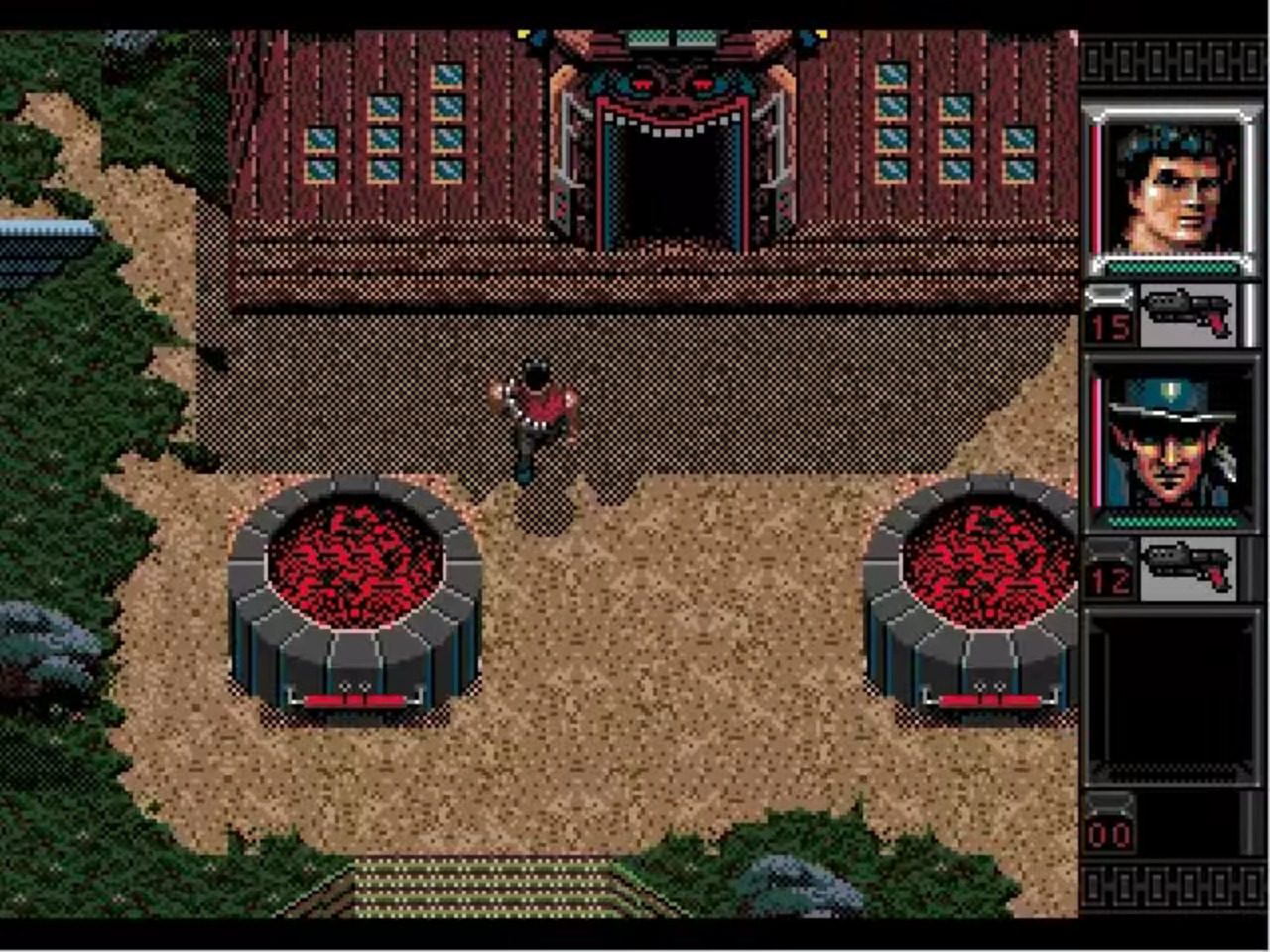

My introduction to it was way back as a child, when I was deeply perplexed by the Shadowrun SNES game. That version still holds a place in my heart, but eventually I got down to playing the one on Genesis. Released in 1994, it is completely and entirely distinct from the SNES version. But while I love the SNES version, the Genesis version, to me, is a prominent part of the console’s landscape. If a montage plays through my head whenever someone mentions the system, Shadowrun features prominently.

However, like the SNES version, it’s not perfect. In fact, I’d say it’s even less perfect than the SNES version. At the same time, it’s more intriguing.

The year is 2058, Seattle UCAS. You play as Joshua, whose brother died in an ambush while on a shadowrun. He vows revenge against whoever did it, because that’s how things go in the cyberpunk future. People just wait around until they have the opportunity for vengeance. Shopkeepers have high overhead because people keep kicking down their door and demanding to know where people are located. The story to the SNES game was technically based on revenge, and so were the three Hairbrained Schemes titles to different extents.

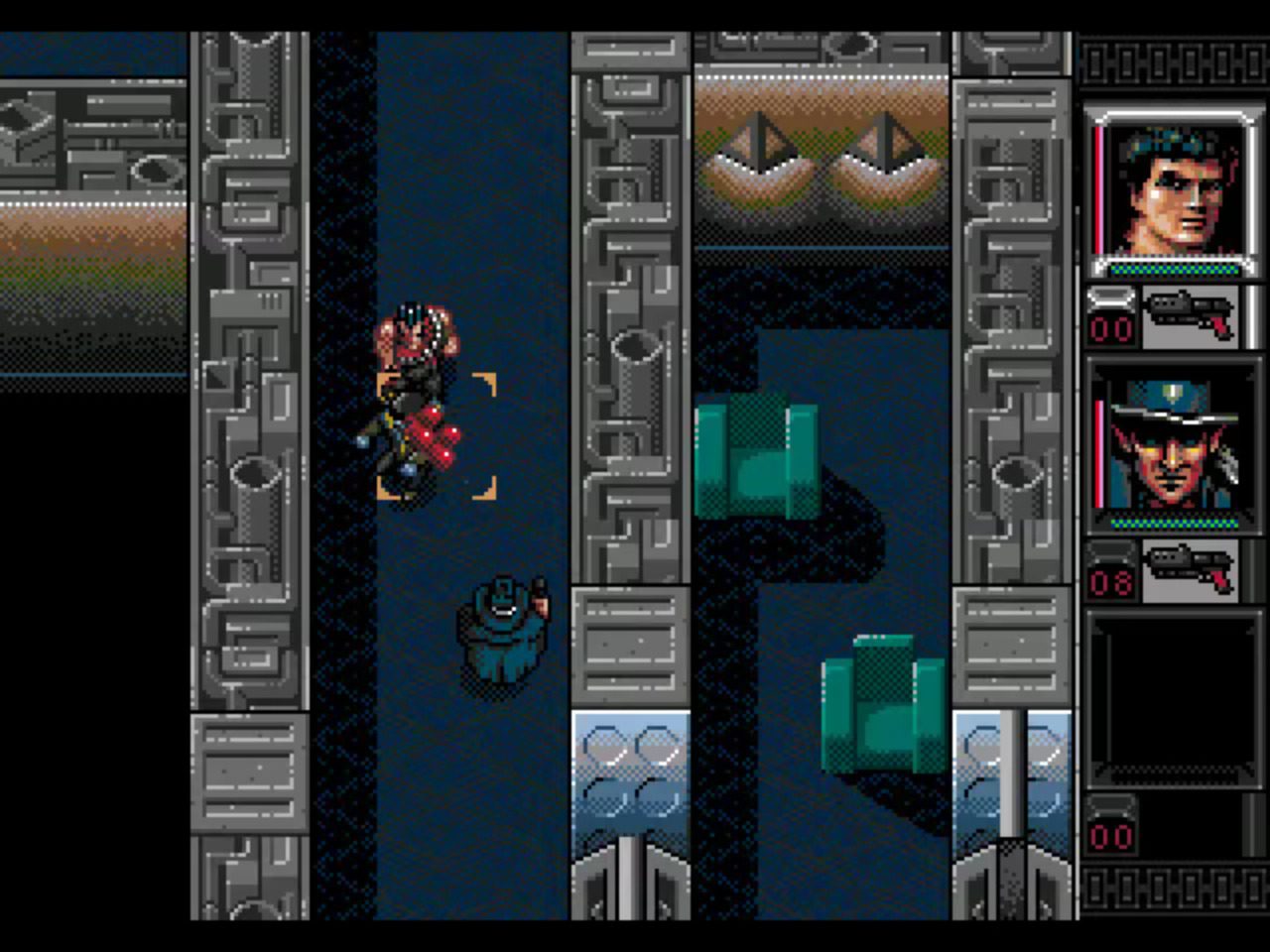

Anyway, where Shadowrun on Genesis differs from the Super Nintendo version is apparent right away; it sticks pretty firmly to the tabletop games. At its core, it’s an open-world game, and it’s pretty ambitious in that regard. You start at the bottom and work your way up until you can take on the game’s later challenges.

At the beginning, you’re mostly going to be grinding for better equipment, because almost everyone can kick your ass. Hold on, what’s Shadowrun slang for ass? “Hoop?” Yeah, that’s terrible. I’m not using that.

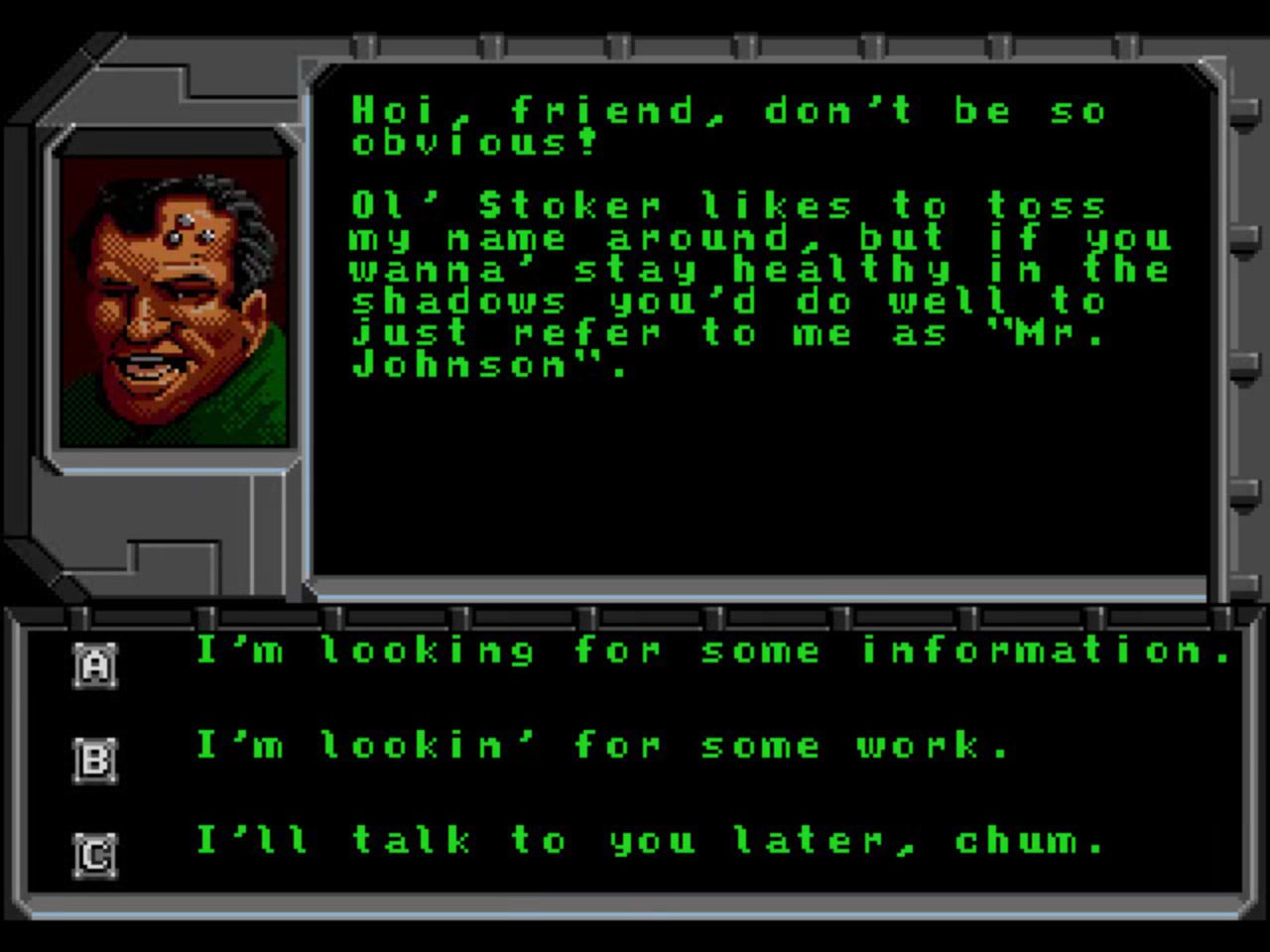

Like your standard tabletop setup, you work for a series of “Mr. Johnsons” who give you random tasks. You begin with low-level tasks like escorting people, delivering packages, and killing zombies, and move up to extracting employees from their megacorporate overlords. Moving up these ranks isn’t your primary objective, but it is the best way to gain karma (experience) and nuyen (money). This winds up being one of the title’s biggest weaknesses, but we’ll get to that.

The real objective is to figure out what happened to your brother, and Shadowrun’s approach to narrative progression is rather ambitious for its time. There are, essentially, three plot threads to follow, and while you have to wrap them all up to see the end, you can tackle them in any way you please. You get leads and contacts that pull you along the path, but if you feel like going off and building your character or engaging a different character, it’s up to you. You set the pace of your progression; well, you and your character’s capabilities.

You can also recruit other runners, which works a lot better than the SNES version’s babysitting simulator. You can hire them for a single run or on a more permanent basis, and if the mission goes to drek, you can just apologize and re-hire them. It helps you make up for skills your character doesn’t have, so if you haven’t picked up any decking, you can just hire a decker to cruise the matrix for you.

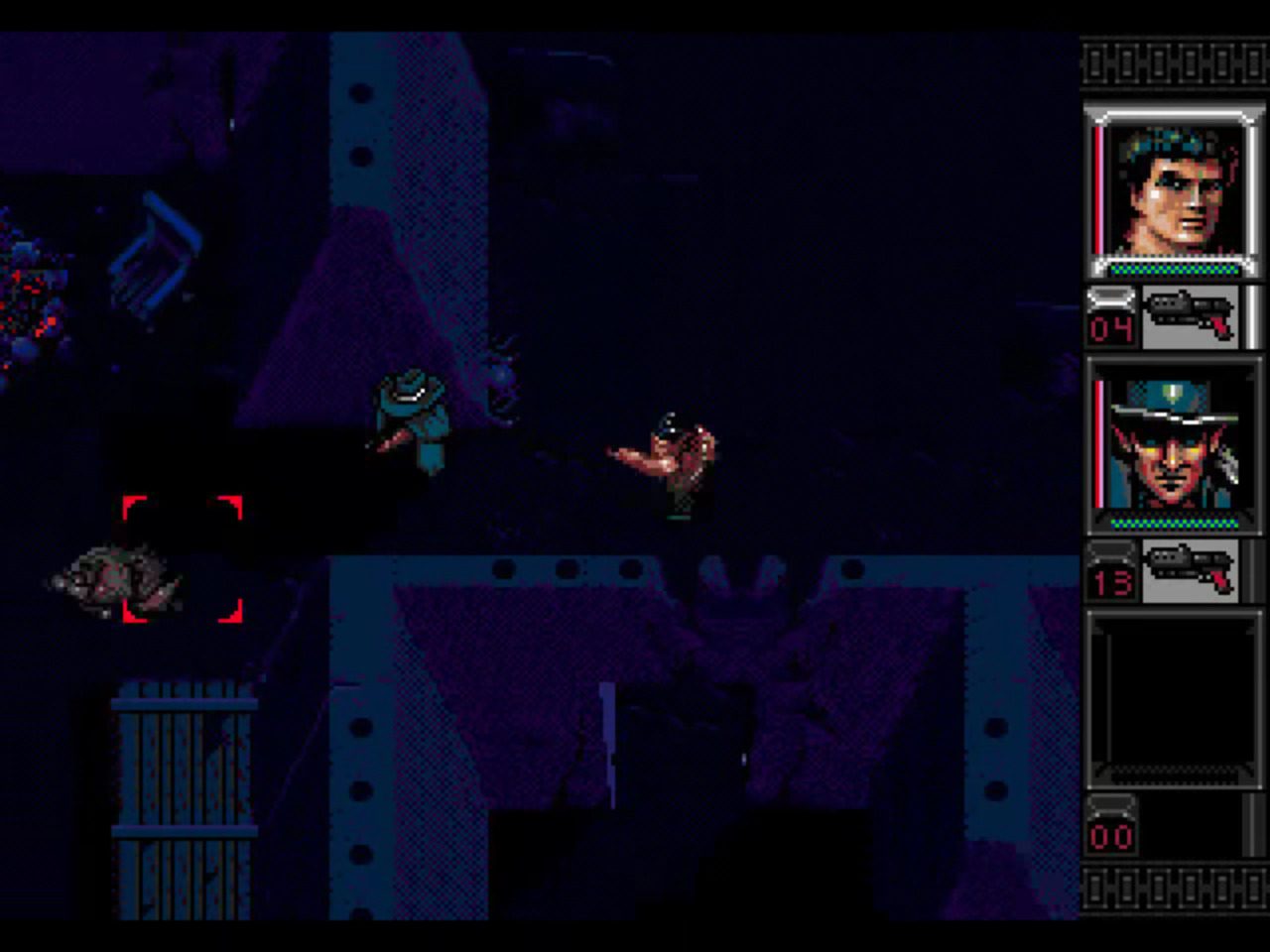

It’s perhaps because the game is so accommodating to different playstyles that it becomes extremely unbalanced. You can start as a shaman, a street samurai, and a decker, and the decker is plainly the worst choice. Gear for surfing the matrix is prohibitively expensive, and working your way up to it while building your skills means grinding. Decking is almost an end-game skill. You can make a tonne of money ripping files out of megacorp databases, but getting to the point where you’re not getting dumpshock each time you jack in takes a lot of time and effort.

Not that you can avoid grinding, which is Shadowrun’s other issue with balance. There are essentially three levels of Mr. Johnson available to give jobs; low, mid, high. It’s almost pointless to go with the mid-tier Mr. Johnsons because the risk is not worth the reward. Their missions are almost as dangerous as their high-level brethren, but they pay less.

No. Instead, you’re going to grind Gunderson in the Redmond Barrens like a pepper mill, sucking in the karma, until you can get in with a high-tier Mr. Johnson. Probably Caleb Brightmore. You do his crappy escort missions, build up your Charisma so he’ll pay you more, then grind them some more, occasionally doing the odd ghoul hunting mission when the pay is right. Rinse, repeat, try not to get bored.

It’s not a complete deathblow to Shadowrun, it’s just really easy to be either over-powered or under-powered with little wiggle room between, and getting from one to the other can be a chore.

There’s a couple ways to mitigate this: First, don’t choose decker. If you want to be a decker, choose street samurai. The funds for better decking equipment are easier to come by if you’re ready for some wetwork. Secondly, don’t focus entirely on one thing. Tackle bits of the narrative, then pause to build your character, then repeat until you’re finished. It will help keep you from getting bogged down.

If you do this, Shadowrun becomes one of the most weirdly engrossing games on the Genesis. It’s an open playground for you to fulfill your cyberpunk fantasies.

While Shadowrun on the SNES could lean on its strengths of its atmosphere and soundtrack, the Genesis version is just compelling in its design. There’s a lot of debate around which is the superior version, and while I tend to lean towards the SNES version, I can’t help but love what landed in Sega’s salad. The level of freedom and how deftly it translated the tabletop RPG absolutely fascinated me.

It’s hard to get past how uneven it is. Two earnest attempts at completing the game were abandoned; bogged down by grind and character building. We finally consummated and I don’t regret a thing. It’s a unique title that is absolutely worthwhile despite its missteps. Again, I don’t think we’ve seen an absolutely perfect Shadowrun title, but at least most of them are worth a look.