A cycle of life, death, and game jams

The first iteration of Loop Hero didn’t come together on time. The latest game from the Four Quarters team started out as a game jam entry in Ludum Dare; the only problem was, by jam’s end, it didn’t really work.

On the page for what was called “LooPatHero” at the time, the team says they ran out of time for the 45th Ludum Dare, whose theme was “Start with nothing.” And you really did start with nothing, starting a loop as an ambitious hero questing to take down the evil Lich.

Two weeks later, Four Quarters updated the page with a working build, including new sprites and a modified combat system. And on March 4, 2021, the team would launch a full version of Loop Hero that would become fairly successful on Steam, selling 500,000 copies in its first week on the platform.

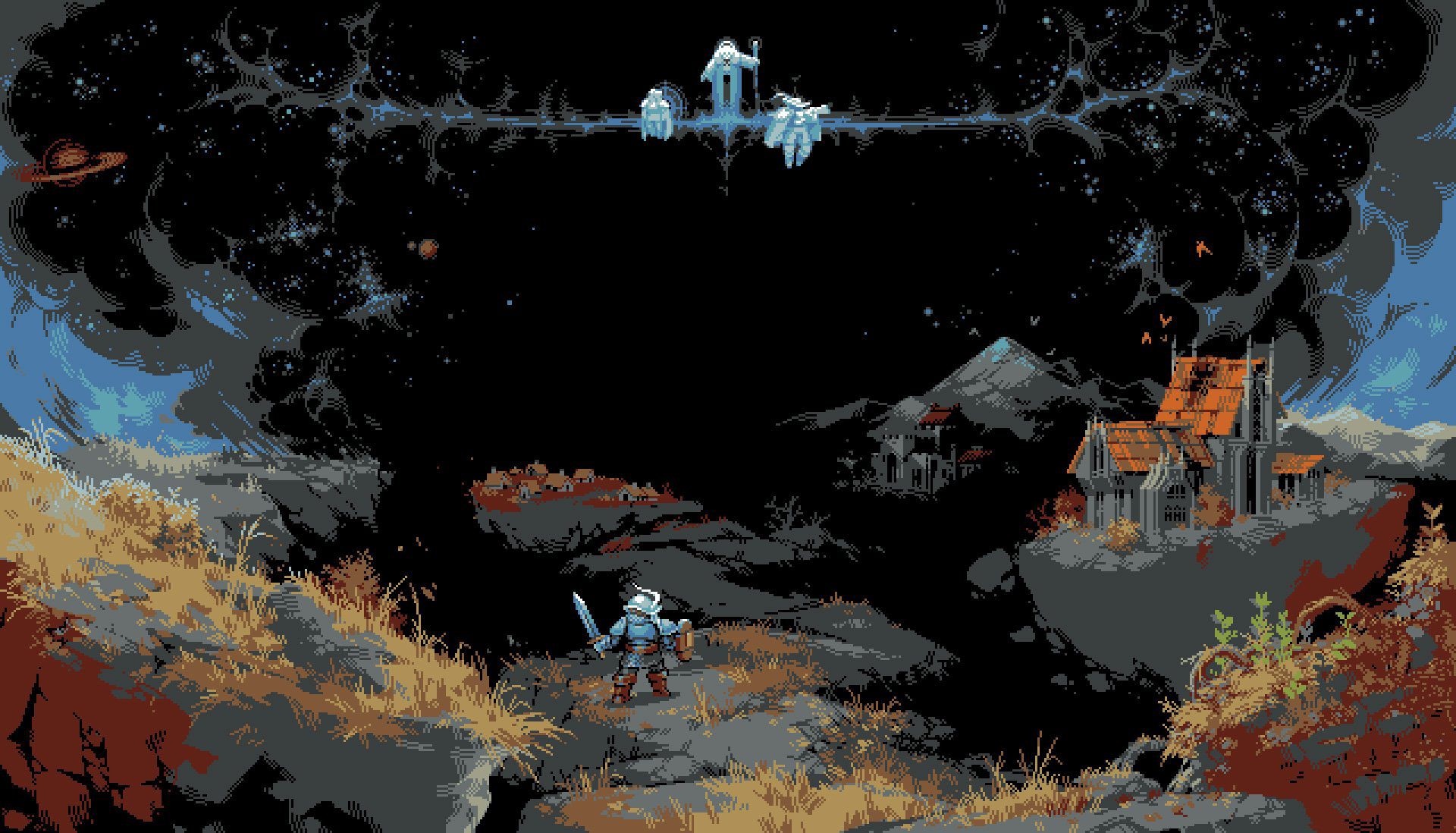

Loop Hero is a continuously looping game, best described as the mash-up of idle games and management sims with the constant progression of a roguelite. The hero wakes up at camp and starts walking in a circle around the loop, and you can play various cards onto the field as tiles that will morph the world and place new challenges in the hero’s path.

While the player controls what equipment the hero wears and traits they earn as they level up, combat is all done automatically and the hero always presses forward until they’re either told to retreat or fall in battle. The idea is to basically play DM to your questing adventurer—placing just enough challenge ahead to not kill them, but make them stronger.

It’s pretty similar to a roguelite, but according to one of its developers, Four Quarters didn’t think about doing a roguelike in the first place. Aleksandr “blinch” Goreslavets, who worked on several aspects of the game but primarily served as composer, says the idea came from the concept of the Loop.

“We discussed the genre of ‘Zero Player Games,’ and our artist [Dmitry “Deceiver” Karimov] created the idea of a Hero who walks in the Loop,” Goreslavets told Destructoid in an email.

The elegant simplicity of Loop Hero stems from this concept of a hero, wandering forward forever, and the player tasked with laying track out in front of them already makes it interesting. But what’s kept me coming back has been the combinations—tiles don’t exist in a vacuum, and part of the Loop Hero magic is discovering how different tiles interact.

Place a lot of Mountains, and the world will spawn an encampment of Goblins. If the Mountains are in the right placement, they’ll also form a peak that’s suited to harboring Harpies, which will start to fly down to hunt on the loop. Treasuries provide huge potential for resources, but an empty one—with every tile around it occupied—becomes a haven for Gargoyles, which can be tough for a low-level hero to deal with.

Balancing the placement of tiles, to gain resources and up the difficulty without sending your hero into a certain doom, is the balancing act at the heart of the loop. These combinations came about as a way to add more interest, as Goreslavets tells it.

“For example, Meadows were initially placed anywhere on the map and there was no special strategy in their placement,” Goreslavets says. “Then we added a combination where if the player placed them next to other tiles, they began to give 50% more healing, which radically changed the principle of placing this card.”

Getting to the end of a loop, and fighting the many bosses laid out in front of the hero starting with the Lich, might seem like the first goal. And yes, at first, the player will die a lot in pursuit of their first Lich kill. Over time, though, a build emerges; you learn to manipulate the tiles to your own benefit. Maybe a Blood Grove could counteract the healing of a Vampire-infested tile, or perhaps placing enemy generators under a Lantern’s radius can limit how big the stacks get.

Killing bosses like the Lich is where the lore plays in, and though Loop Hero‘s story is sparse, it works to its benefit. There’s something hauntingly intriguing about its world reduced to almost nothing, a void in which you’re reconstructing new versions of itself. Karimov was responsible for the main lore of the game, as Goreslavets tells me, and the plot was written to answer why everything looks the way it does.

Because of this, bosses act as “anchors,” as Goreslavets calls them, around which the plot advances. And beyond just killing an escalating list of giant adversaries, the Camp adds a sense of meta-progression. It was a way to change up the long-term of the game, as the core loop of the Loop is always the same—its shape may change, but there will always be a loop with vacuous space for tiles to be placed.

The Camp is also where resources come into play, and it ends up acting as a boon for players who are struggling with advancing on their own. While Loop Hero‘s additional classes and other abilities are unlocked through the camp, it’s also where you get bonuses to help make future runs easier. Healing flasks, a smattering of free items at the beginning of each run, and new tiles to bolster existing combinations are all gained through the Camp.

When I ask Goreslavets about how other roguelikes have been implementing assist modes—for example, Hades‘ God Mode—he refers me to the Camp. “Loop Hero doesn’t have any option for it, but we don’t ‘punish’ players for losing,” Goreslavets says. “Even if the hero dies—they will take some resources to their camp to upgrade some buildings. We didn’t want players to feel afraid to experiment or punished for ‘ineffective play.'”

The result has been a surprise hit for the team, previously known for their work on Please, Don’t Touch Anything. Goreslavets says the team is shocked and still surprised by Loop Hero‘s reception; “We really liked the game, but did not expect that such a large number of people would like it too,” he says.

As for what’s next, it’s a lot more Loop Hero. They had a lot of ideas left for post-release during the making of the game, and now they’re starting to implement them. Though Goreslavets says it’s too early to say what exactly will make it in, they drop a hint towards a recent tweet of some art as a new enemy.

Four Quarters is made up of four people, all in different cities and working from home, so the pandemic didn’t affect any sort of in-person workflow. It still, of course, had other effects; there was a lot of “overall stress” due to the pandemic, Goreslavets says.

Still, the team finds time to play games together alongside developing them. They play Monster Hunter and Dota 2, and in one surprising turn of events, found a much-needed boost in another roguelike.

“At the end of 2020, at a late stage of development, the work was very intense and we started to burn out,” Goreslavets says. “Then we accidentally discovered ‘Slay the Spire.’ This is a gorgeous and genius card roguelike which helped us relax in the evenings, when we gathered in Discord and took turns trying to beat it.”

For the even further future, Four Quarters still has plenty of ideas. The team has made 15 games for Ludum Dare, spanning several different genres: from a Russian roulette RPG to a rhythm game about kaiju attacks, they’ve got ideas.

Even Four Quarters does not know what will be next, Goreslavets tells me. But if Loop Hero has shown anything, it’s that any one of those 15 ideas is certainly worth keeping an eye on.