Why people care about Mother 2

[Image by Anonymous]

EarthBound was re-released on the Wii U Virtual Consoles this week, with off-TV play and online access to the packed-in strategy guide from the game’s original 1995 release on the SNES. Many fans of the game were overjoyed, while many more took one look and said, “You want me to pay $10 for this?!?” They may have grown to love Ness from his appearances in Smash Bros., heard about the game’s influence on the creators of South Park, seen the amazing merch from Fangamer, or read one of the many brilliant essays on the subject, but when confronted with the actual opportunity to buy the game, they were left cold.

The sad fact is, EarthBound isn’t any more marketable today than when it initially failed to meet sales expectations back in the ’90s. Though Nintendo was wise enough to avoid telling the world that the game “stinks” and is “garbage” this time around, the underlying barriers between EarthBound and the mass market remain the same. It’s very hard to see from a distance what makes the game so great.

Here’s my best attempt to give you an up close look at why this game means so much to so many.

The granddaddy of modern surrealist adventure games

The first time I played Pokemon, I thought, “Cool. This is like the new EarthBound.” The similarities were everywhere, from obvious traits like the striking resemblances between the player characters, to “boy sets out on his own in a big adult world for a vaguely aimless adventure” theme, to the sense of humor, art direction battle system, and even the bicycle.

The same thing happened when I first played Animal Crossing, and Majora’s Mask, and Chibi Robo, and Snowpack Park. Almost every “quirky” Nintendo game released after 1995 seems to have some tonal or thematic link to EarthBound. It seemed to play a major role in forming the company’s narrative identity.

The game’s presumed influence doesn’t stop at Nintendo franchises. Persona feels a lot like EarthBound with skinny teenagers. Others have drawn parallels between EarthBound and No More Heroes, Retro City Rampage, Homestuck, and even the more ridiculous parts of Grand Theft Auto. The validity of those comparisons are subjective, but there is no questioning how much more EarthBound stood out from the crowd in the ’90s than it does now. Fifteen years ago, nearly every videogame was a work up of some manga, Tolkien, or Western sci-fi/fantasty convention, and they almost never tried to be funny.

EarthBound sends the message that the real world was just as compelling and extraordinary as any fictional world you could dream up, and it sent that message with a decidedly irreverent comedic bent. It was a wildly risky departure from convention, one that paved the way for many of the franchises that we take for granted today.

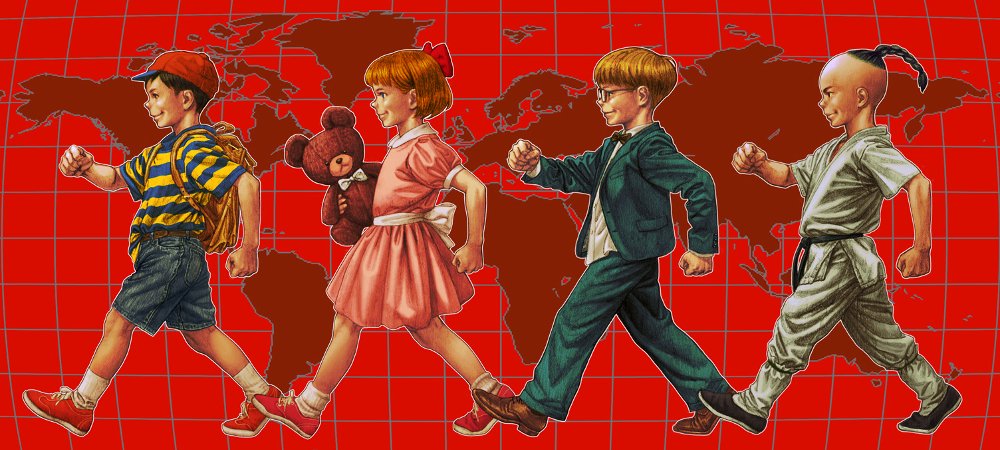

Being a child doesn’t have to be childish

One of the main things EarthBound has going against it in terms or marketability is its mismatch between target audience and its surface-level appeal. It’s a simple-looking game about children, which implies that it’s a simple game for children. Like many of Nintendo’s best properties, there is plenty for kids to enjoy in EarthBound, but it’s not a “kids game.”

EarthBound is a reflection upon childhood from an adult’s perspective. The game has been compared many times to Catcher in the Rye and works of Maurice Sendak, and for good reason. In EarthBound, the children are the genuine, selfless heroes and the adults are the ridiculous, misguided, hubris-laiden fools, caught up in classism, selfish ambition, and immaterial goods like “money” and “power” (but more on that later).

It’s all made more pointed by the fact that it’s coming from a child’s vantage point. While it’s easier to see a child’s place as initially disempowered and unattractive, their starting point of weakness only extenuates their displays of strengths. When Robin takes on a room full of gun-toting criminals, it means more than when a full grown man dressed as a bat, armed with years of training and millions in body armor does the same. The same could be said for all the children of EarthBound achieve (even that little jerk Pokey).

A masterpiece of rebellious craftsmanship

EarthBound does not look impressive, but the game’s unified melding of music, writing, and visual design is masterful. The tone of sweetly strange obliviousness to convention is retained in every aspect of the game. The graphics often look like discarded doodles from a technically accomplished artist’s sketchbook, which matches perfectly with the reams of NPC dialogue that lack even a hint of self-awareness or self-consciousness. The music similarly defies conventional characterization, coming across like the sonic sketches from a composer who is skilled to the point where even their most effortlessly constructed melodies are endlessly infectious.

Beneath all that is a turn-based RPG that works to correct many of the genre’s flaws. Unlike in Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, or many other RPGs of the time, enemies appear outside of the battle scene, allowing the player to try to avoid them or even surprise them before battle. Even better, when you enter combat with an enemy that’s far below your experience level, the combat ends instantaneously, netting you the XP and potential item rewards with none of the potentiality tedious combat.

EarthBound focuses on minutia but never feels trivial. Everything in the game, from the dialogue of the most inconsequential NPC to the overworld sprites of the tiniest attack slug, feels intensely cared about while defying the status quo at every turn.

A candy shell concealing a deep well of humanity

EarthBound was originally released before the ESRB was in full effect. In 1995, it was rated KA (Kids to Adults). In 2013, it was rated T for teen. My guess is that upon initial review, the game was only scanned for nudity, blood, and swears, providing it with a “kid appropriate” stamp of approval. Somewhere along the line, the ESRB must have noticed all the stuff about America, politicians, post-traumatic stress, corporations, depression, capitalism, homosexuality, religious cults, and xenophobia. While I don’t agree with the assessment that EarthBound is in any way inappropriate for children, I could see why some of this stuff could be seen as a little strong for some kids to process.

It’s hard to get into the better details without spoiling them, but I really want to. I really want to let you know that the last hour of EarthBound has had me thinking for years about my relationship with videogames, victims of child abuse, the meanings of evil, heroism, religion, and life in general.

I get why some people are angry that EarthBound is being sold for $10. It feels to them like Nintendo is selling them something that they could provide to the consumer for much less without suffering any financial burden. That said, I’m glad EarthBound costs what it does. I may be even happier if it cost more. This game has value. There should be no ambiguity about that. If you have any interest in poetic, experimental, heartfelt, satirical, or culture-critical games, then you will appreciate EarthBound. It does what it aims to do in a flawless manner. If that’s not worth $10 (or more) then nothing is.