What the hell is gay coding?

As one of those fellas who likes fellas, I have to feel pretty lucky for the point in human history in which I am being allowed to exist. As an infant of the ‘80s, a child of the ‘90s, and an adult of the aughts and beyond, I have been witness to some of the best and worst of LGBTQ history. My life started in the panic of the AIDS crisis and as I’ve grown up, I’ve seen how quickly society has evolved to be more inclusive of my peeps, taking them from the butt of the joke to the stars of the show.

I used to thank lesbians for paving the way for the rest of us. My memories of early ‘90s entertainment are very heavy on lesbians, from Carol on Friends to Christine in The First Wives Club to basically every music video featuring a white woman with a guitar on VH1; lesbians were very en vogue. My thought process convinced me they got their Birkenstocks in the door to create an opening for the rest of us. As I’ve grown and researched more of my culture, I’ve come to learn the path to where we are today started decades before the era where hanging out in coffee shops wearing chunky fall color sweaters was the hippest thing to do. That’s because, over the past couple of years, I’ve been learning more and more about coding.

Not useful coding, like Python or anything, but gay coding. The practice where characters are given traits identifiable to members of the LGBTQ community without explicitly stating they’re gay. That’s right, I only learned about this roughly four years ago. Think about all the decades of cuffed jeans, bisexual lighting, and pinkies up I’ve missed over my life. I’ve been exploring the concept of coding in film over many months as I’ve visited the classic films I somehow missed in my cinephile college years. More recently, it’s been something I’ve been actively looking for in games.

Because I have grown up in an era where gay characters can just be gay on TV and in movies, and where plenty of RPGs have let me craft my own little homo adventures, I’ve started to question why would even need to utilize gay coding anymore. I mean, if the world is as accepting as it presents itself to be, do we really need to hide our intentions behind sly references?

Lofty ambitions

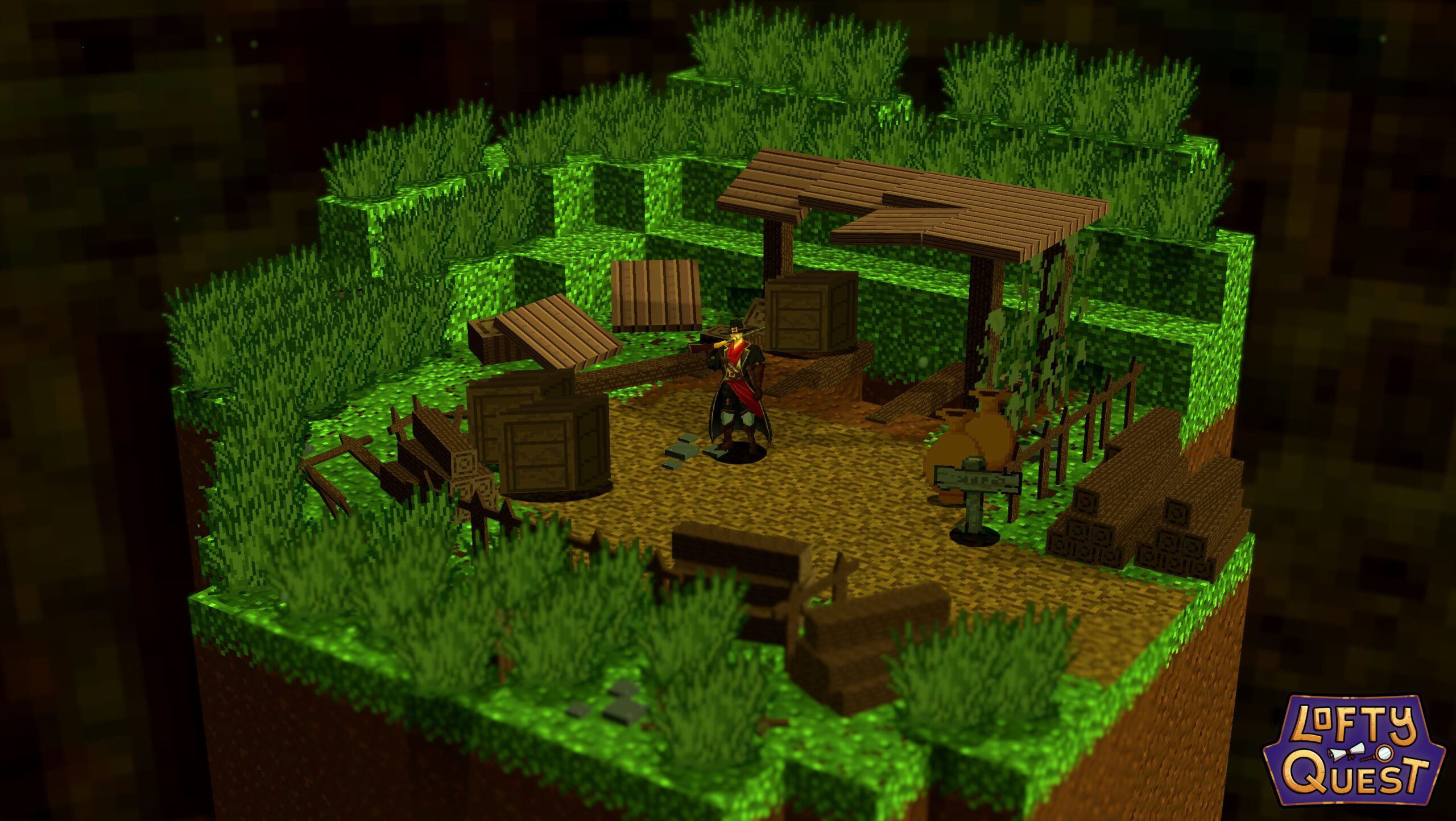

That is why it must be kismet that indie developer Devon Wiersma got in touch with me after I put out feelers for a new LGBTQ column I’ve wanted to start for Destructoid since the beginning of the pandemic. Wiersma is currently working with indie outlet The Beans Team on an unannounced project and has worked in the past with Cococucumber, developer of Echo Generation, in addition to a stint at Ubisoft Toronto. Wiersma also develops solo projects on the side, including Bombing!!: A Graffiti Sandbox and the upcoming Lofty Quest, a hidden-object game featuring 3D dioramas that originally started as a college assignment known as Lofty.

“I’m a level designer by profession and I’ve always enjoyed setting up little dioramas and scenarios with my sister’s paper dolls and my army men,” Wiersma explained, “so to me, Lofty was just as fun to create scenes for as it was to play.”

For Lofty Quest, the successor to that college project, Wiersma has to go bigger. More objects to find, more dioramas to explore, and more ways for the player to connect with the game. That original college project never strayed too far from Wiersma’s mind, but expanding on that initial idea would require a deconstruction of what made it work in the first place, as well as an exploration of the hidden object genre at large with some choice recommendations from a trusted source.

“My partner is a long-time fan of the Dark Parables games,” Wiersma said, “and she helped introduce me to a lot more traditional digital hidden object games I wasn’t familiar with. One thing this process helped me realize was there a lot of the time the hook for these games was the story, and Lofty really didn’t have any of that. There wasn’t any narrative to speak of, and you never really had a sense as to why you were looking for the things you were looking for. The whole game felt a little aimless as a result and was something I wanted to improve on. I started to plan out a plot and more interesting ways you could engage with this world, and soon Lofty Quest was born.”

Just how gay is it?

Wiersma settled on a story of a protagonist named Sister Jessica working with a band of heroes to topple a corrupt king. Usually, it’s in the design and histories of a game’s characters where players would most be able to recognize its queer intentions. It’s difficult to look at something like Get in the Car, Loser!, If Found…, or Dream Daddy and not immediately see their queer intentions right upfront. But Wiersma is taking a different approach and instilling LGBTQ themes into the game using gay coding.

“I don’t make a habit of calling Lofty Quest a queer game when talking about it,” Wiersma explained. “It doesn’t deal with or address queerness directly. None of the characters are established to be in relationships. None of the character’s orientations or gender identities are ever talked about or even really elaborated on. These are things I’ve worked with and established in developing the game, but the game never addresses them explicitly, largely because those facets of the characters aren’t what the game is intended to be exploring.”

“All that being said, I absolutely consider all of the works I create to be queer works. I’m a queer creative, and I believe everything I make is reflective of myself, my values, and who I am as a person. Narratively, Lofty Quest overtly deals with themes I think will resonate with queer people most – found family, fighting systemic failures, knowing who your allies really are – things like that. I think my work tends to ‘pass’ as non-queer digital media, but they’re queer beneath the surface and I consider them as such.”

Passing as non-queer is the story of my life. Nobody seems to be able to tell that I’m a flagpole sitta just by looking at me, and unless you catch me dancing to Debbie Gibson in the shower, my mannerisms don’t really speak volumes about who I am. And I get how it is to skate through life not experiencing any noticeable level of homophobia from the outside world, which is why it’s easy for me to relate to not only how Wiersma is choosing to present Lofty Quest, but also the unfortunate benefits of doing so.

“I’d be lying if I said I didn’t use this ability to “pass” as a standard game as a safety net to give plausible deniability in the face of criticism or harassment too,” Wiersma said. “My previous game, Bombing!!: A Graffiti Sandbox, was a creative sandbox game where you can spray paint anywhere. I think it has a subtextual appeal to queer players, and that was something I was conscious of as I was making it. I went back and forth on adding the ‘LGBTQ+’ tag to the game on Steam for a long time and ultimately decided against it shortly before release because it felt like a potential risk to myself. Turns out I made a good choice, as not long after release some Steam users submitted screenshots of anti-queer art they made in the game, which I obviously had to flag for removal. That personally wasn’t a very pleasant moment for me but also felt like validation that I didn’t put a target on myself.”

Gay coding goes back quite a ways

It’s that kind of toxicity in the world that can make me understand why an LGBTQ creator would want to use gay coding in their works rather than deal with the stress that can come with presenting an openly queer game that could end up in the crosshairs of the wrong people. In fact, it’s how I imagine the whole idea of gay coding got started in the first place. I’m not sure of its exact origins, but there is a beautiful documentary short available on Paramount+ right now covering gay coding in 20th-century advertising.

It focuses on J.C. Leyendecker, who was an artist in turn-of-the-century New York City most famous for his work with The Saturday Evening Post and Arrow Collars. With the latter, he more or less created the concept of the sophisticated, ideal American man. His paintings featured slender, attractive men, some of whom were modeled by his partner Charles Beach, exchanging enough wayward glances and longing stares to tell the exact story Leyendecker wanted to tell to the open and closeted men of America. The Arrow Collar Man was somebody that men wanted to be, women wanted to be with, and gay men wanted both.

It’s actually kind of interesting how queer-friendly things were in the early 20th century. I mean, not like they are today but certainly worlds better than what it was like following the Great Depression. Morals and all that religious nonsense really came back into fashion then. The wild west of Hollywood was brought into line too with the Hays Code, setting back the advancement of the LGBTQ community. But code or no code, gays would continue to flock to the more welcoming arms of the arts and entertainment industry. As they did, these writers, directors, producers, costume designers, and even actors spent decades sneaking queer culture into the mainstream.

From the limp-wristed sissies who were there for a laugh to the butch women who could handle a six-shooter like nobody else, straight audiences may not have been totally kosher with positive or even neutral representation of gay characters in cinema, but chances are most of them were too thick to recognize it. I mean, just think about how many women thought Liberace just needed to find the right woman or how millions of people watched Tony Curtis and Laurence Olivier talk about eating oysters and snails in Spartacus, a scene so gay it makes Brokeback Mountain look like Def Jam’s How to Be a Player.

All of that and more are just classic examples of how queer characters and queer culture have been coded into seemingly straight entertainment. Like with Wiersma, when you have queer creators working on a project, chances are they will inject part of their identity into what it is they’re creating, even if it’s not explicitly for queer audiences.

“That’s a large part of why I call my games ‘queer-coded’ and not resolutely ‘queer’, Wiersma said. “By and large they aren’t about being queer, but they’re made with a queer lens which influences their creation at every step of the way. I think this is in part because this approach to queerness is one that resonates with me – situations and scenarios where queerness exists in the world, but it never has to be the calling card or the focus, it just is alongside everything else.”

Arguably, many other game developers approach LGBTQ representation in a similar fashion. While there are queer-oriented games on the market, it’s not hard to see gay-coded entertainment if you know what you’re looking for. The Industry’s Chris Moyse and I were talking about the subject and he called Hades a blatantly bisexual game. And really, I can’t argue with that assessment. EarthBound has an NPC named Tony who’s a very best friend of Jeff and who just repeats Jeff’s name when players find him later in the game. For LGBTQ players, it would be easy to see Tony for who he was at that exact moment. For everyone else, EarthBound creator Shigesato Itoi confirmed in the years following the game’s release that Tony was in fact a gay child. Tony may not be the most dynamic NPC found in EarthBound, but his inclusion was certainly a lot better than most of the representation we saw in the ‘90s. Nintendo is arguably the last developer you’d expect gay-coded entertainment out of, but it also makes the Animal Crossing series, which has been pretty damn queer since its debut.

But is it actually coded or am I just horny?

Also, what about Miles Edgeworth or Cabanela from Ghost Trick? They seem pretty gay coded to me, though I do worry about whether or not I’m seeing something that isn’t actually there, a situation where I’m imprinting my own thoughts and desires onto a piece of entertainment where it doesn’t actually exist. I think back to my senior year English class in high school where the teacher dug into the subtext of Bassanio and Antonio’s relationship in The Merchant of Venice. Maybe Shakespeare did intend for these two characters to be the Bert and Ernie of their day, but for me, the text of the play didn’t lead to that conclusion.

On the other hand, I took one look at the box art for Conan on NES and decided that was shit was gay as hell. I know the muscular shirtless guy with a big sword and shield is supposed to be a male power fantasy, but I would argue it’s also a male power bottom fantasy. Sometimes, it’s just all in the eye of the beholder.

“In Bully, for example, Jimmy Hopkins is a bisexual protagonist – he can kiss girls or guys all the same. It’s never mentioned in the plot and it’s never overtly taught in the mechanics of the game that you can kiss boy students – it’s almost like a hidden mechanic you have to discover yourself. It’s super minor and a bit off the beaten path. All the while, that game’s plot dances with themes of self-discovery, toxic masculinity, and fighting back against systems that don’t want you to exist. To most people Bully passes as a straight game (maybe an incredibly straight one at that) but to me, a queer person, it absolutely is a queer game, even if it doesn’t overtly wave that flag.”

Bully is a great example of how developers can make their mainstream-oriented games friendlier to LGBTQ audiences without explicitly advertising those titles as queer. And like with what Wiersma is doing with Lofty Quest, it doesn’t have to be with something as direct as kissing other boys. Sometimes it can just be the themes presented to players that LGBTQ players will easily recognize and associate with. Or they can just go all in and give you the black screen of gay sexual pleasure like Fable did nearly 20 years ago.

Be careful not to turn coding into baiting

It’s amazing to think just how quickly LGBTQ representation has progressed from the gay marriages of Fallout 2 to fucking EA refusing to remove a same-sex couple from the cover of the latest Sims expansion. Even before indies were pumping out niche queer games with regularity, AAA developers expanded on the type of explicit representation that was allowed into their games. However, as Wiersma points out, such representation isn’t always done with the greatest of intents.

“AAA companies have so much power and so many resources at their disposal; they are in the best position to push progress forward by making informed and explicit representations of people from all walks of life. Unfortunately, queerness in the AAA sphere tends to feel like queer-baiting by companies who want money from queer audiences without doing the legwork to make the representation meaningful at worst, or at best small crumbs of representation by members of the team who barely managed to sneak it through the straight white guy studio executive filter.”

“To be clear: if AAA studios wanted to be welcoming to 2SLGBTQ players then AAA studios would have no problem being explicit in their representations. I don’t believe AAA developers, of all people, are in a position where they should have to resort to using queer coding. AAA companies would really often prefer to queer code things instead of being explicit because that would require them to fundamentally change their approach to representation, which isn’t something I think many of them have a vested interest in doing. Outside of generating some good PR, it would require redirecting resources into hiring queer consultants, actually progressing towards pay equity of marginalized employees, and generally rethinking their entire approach to how their operations are run from the ground up. As with anything, doing good means fixing things and spending money, and that’s two risks AAA businesses don’t have much of an interest in pursuing.”

Be gay in your own way

With such a long history of struggle for LGBTQ people to be seen in popular entertainment that we’d have to resort to something as “dastardly” as gay coding, it’ll be interesting to see how and if the practice continues and evolves in the future. Times are changing and the industry is a lot more inviting of queer people, even if it often feels like it’s only a surface-level acceptance. LGBTQ-friendly indie games thrive and even Nintendo is allowing explicitly gay characters into Fire Emblem. It would be easy to look at something like The Last of Us Part II and think there is no reason for queer developers to resort to coding anymore, that they can be loud and proud as they want to be in their creations while gaining widespread acceptance and praise.

But looking back at Wiersma’s answers to my questions, I can’t help but feel that gay coding is still a vitally useful tool for queer creators who don’t necessarily want to focus on queer identities for their games. Not only are there the assholes out there, just waiting to announce to the world how much of an asshole they are by targeting said games, but honestly, not every game with an LGBTQ character has to focus on them being gay or put them in same-sex relationships for people to accept and recognize their identity. Sometimes, a dinosaur lady wearing a pink, purple, and royal blue pantsuit is all you need to convey to your audience everything you want them to know.

And just to be clear, when I’m saying this is absolutely still a place for gay coding in gaming, I am of course talking about positive or neutral uses of the practice. I know that, traditionally, gay coding has been used on villains more than it has the hero, and while there are some great gay-coded villains I love, I’m also pretty bored of that being the standard.

Lofty Quest is currently in development for PC and is expected to release this summer.