Filling in a cultural gap

I have a confession to make: I missed out on Metal Gear Solid. I was a lame kid who liked cartoony platformers and power-of-friendship RPGs, and Hideo Kojima’s epic saga of gruff military boys in cardboard boxes did nothing for my brain. Still, I figured I understood what Metal Gear was based on pop culture osmosis – baffling lore, thoughtful political intrigue, and brief interludes of intense homoeroticism, all in a 3D stealth shooting package.

So imagine my surprise when I went on my very first journey with Solid Snake and didn’t see any of that. See, when I start a task, I like to start it from the beginning. So when I committed to getting into Metal Gear, I went straight for entry numero uno: 1987’s Metal Gear for the MSX 2.

Humble beginnings

Metal Gear is a game about a guy named Solid Snake, a rookie agent for a military organization known as FOXHOUND. I will admit, I don’t know much about Solid Snake in the Metal Gear Solid games, but to the best of my understanding, he’s a character in those games. To call him a “character” in Metal Gear would be a little generous. Mostly, he’s a two-inch tall computer man who just loves infiltrating. He can’t get enough of infiltrating! It’s his favorite thing to do.

Snake’s second favorite thing to do is pick things up and take them somewhere else. He takes after Metroid‘s Samus Aran in this way; he’s always finding an object in one place that makes it easier to navigate another place. That’s great, because Snake’s current mission is to infiltrate Outer Heaven, a very sinister mercenary stronghold in South Africa that’s full of objects that are absolutely vital for navigation. I’m not sure how anyone actually gets any work done in Outer Heaven, given that multiple connecting rooms fill up with toxic gas for no reason in particular and there’s only one gas mask.

Most of Metal Gear consists of finding things in one place and taking them to another place. While you’re busy doing that, Outer Heaven mercenaries will try and shoot at you, so it’s best to hide behind the architecturally nonsensical pillars scattered around the base. If you do get caught, it’s probably best to just make a break for the next room over. Most of the time, if the bad guys can’t see you, they’ll fully forget you exist, which is good since Snake is terrible at shooting (it’s possible that I’m terrible at shooting, but I’m going to lay the blame at Snake’s feet here).

But is it any good?

I’m being snarky, obviously, but I actually think there’s a lot to love in this humble little proto-Metal Gear. It’s not what I expected at all, but I ended up having a very good time with it. The stealth is shockingly elegant for a game this old. I figured it would be Clunkfest 1987, but most of the time, if the bad guys caught me, it was fully my fault, and if I caught them, it actually felt pretty good.

Metal Gear has what could be described as a prototypical “stealth kill” mechanic: if you manage to get the jump on a bad guy by creeping behind them, you can pretty much stunlock them and punch them to death without alerting any of their buddies. Actually, you can do that by just walking up to their side, too, provided you aren’t looking them directly in the eye.

Outer Heaven’s boys are not the most attentive.

There are a handful of other ways to get around Outer Heaven — sometimes, agents will fall asleep standing up, and you can walk right past them without issue. My favorite method of conflict aversion, though, is Solid Snake’s iconic cardboard box. The box is introduced with the kind of goofy reverence that suggests that the developers knew what they had on their hands. It’s all alone in an empty room, it has no item description, and Snake’s (spoiler alert) confidant-turned-nemesis Big Boss has absolutely no idea what to make of it. The first time Snake puts it on his head and disappears entirely, it’s like magic.

Wit and wisdom

I also found myself really taken by Metal Gear‘s writing. There’s not much of it, but what’s there was very endearing to me. My favorite characters, hands down, are the captured FOXHOUND agents who spout off some of the most incredible advice of all time. I know when my government-sanctioned action hero comes to break me out of prison, I’m always ready to tell them what they might be able to do if they had a parachute.

Metal Gear also plays host to a lot of authorial instincts that I instantly recognized as a fan of Death Stranding and PT. His ability to bump up against the fourth wall in ways that are simultaneously unnerving and playful is on full display here, as is his willingness to mess around with genre and medium.

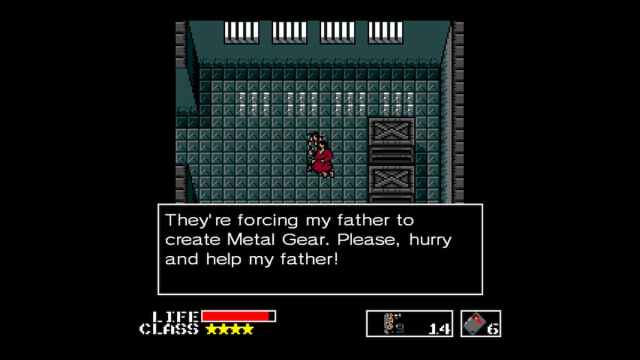

The “plot,” if it can be described as such, is as thin and unimpressive as most games of the era — I got through all of Metal Gear in about three hours, and two and a half of those were dedicated to finding key cards, so there wasn’t a whole lot of time for narrative development. Metal Gear is aware of this fact, though. Its characters are painted in broad, archetypal strokes. Solid Snake is every single action hero. The creator of the eponymous Metal Gear is every beleaguered scientist. The Big Boss at the end is literally named Big Boss. It’s all light genre pastiche, and it’s got a low-key sense of humor that makes it very endearing.

Plus, there’s this girl, who is apparently Hideo Kojima’s daughter.

In the end, I’m glad I finally got around to playing Metal Gear. It’s got plenty of ridiculously dated design decisions, including elevators that take ages to ascend, holes that open in the ground and insta-kill you with absolutely no warning (again, how do people work here?), and a boss fight with one of the worst gimmicks I’ve ever seen, but it was a good time.

I snagged it for a mere five dollars, and honestly, if it was a brand-new game at the same price, I think I’d still really dig it. I’m almost certainly going to chase it with all the other Metal Gear games, and I might just give Kojima’s other MSX-era games a try, too. Maybe I’ll finally get to see some of that intense homoeroticism.