More than the basics of CQC

We stole the instruction manual when we rented Metal Gear Solid from Blockbuster. It’s the one and only time we ever did that. Normally we were fine upstanding rental citizens who held manual-thieves in smug contempt. But in this one case we made the exception and became the very thing we hated.

Which is kind of a Metal Gear thing if you think about it.

My brother and I managed to rent Metal Gear Solid the very first weekend our local store got it. Of course we did. We’d damn near worn out the demo disk featuring the first 20 minutes of Snake infiltrating the Shadow Moses nuclear disposal site in the months before release, there was no way we weren’t picking it up at launch. We wanted to buy it but there was no money, so renting it was. We played with purpose, knowing there was no way we were going to return the game without seeing the mission through to its end.

Metal Gear was something we hadn’t seen before. It was cold, and sleek, and dangerous. It was a war game where you were better off never killing anybody. It was a sophisticated espionage thriller where if you moved fast enough and got good with your binoculars, you could peep on half dressed polygon ladies and watch their butts wiggle. It was a game with a guy who pissed himself in one cutscene and almost made me cry in another.

Suffice to say, it was an experience.

I remember the entire route through Shadow Moses. I remember the area with electrified tiles inset in the floor and steering a tiny rocket over them. I remember resenting not being able to use my guns in the nuke disposal area. The cave with all of Sniper Wolf’s wolves running loose — one of them pissed on my cardboard box. I’ll sometimes forget the best way to get downtown, but the map of Shadow Moses is burned into my memory.

The bosses were legendary, both for their design and the surreal conversations you’d have before, during, and afterward. One-on-one with an old west gunfighter, circling each other around a hostage in the middle of a room rigged up with C4. He showed off his fancy carnival trick-spinning and made comments that distinctly implied that he wanted to make love to his pistol, or that gun fighting was an allegory for sex to him. I don’t know, he was a weird dude.

There was that shaman who you’d fight twice, once in a literal tank and once while he carried around a gun the size of a small tank. He discussed ear-pulling competitions and the futility of struggling against fate. He was eaten by his own ravens. Then there was the suffocating tension and isolation of dueling a single sniper hundreds of yards away. The battle with Sniper Wolf would be eclipsed in every way six years later by Naked Snake’s duel against The End, but at the time it was one of the most intense fights I’d ever experienced.

I feel like there has probably been enough ink spilled on how crazy the fight with Psycho Mantis was, but holy fucking shit. How did any of that happen? It was like stepping into some alternate reality where Andy Kaufman had been a game designer and somebody cut him a blank check.

Memes of plugging the controller into the second slot, or the infamous “HIDEO” error screen are well worn now. But I don’t think secondary accounts can do justice to just how crazy and bizarre that fight, and the rest of Metal Gear Solid, truly was. All of that weird fourth wall breaking shit — holding the controller to your arm for a massage, having the Colonel explain combat maneuvers to Snake directly referencing the DualShock and a bunch of video game jargon, it was something that had to be lived in the moment. It felt like Kojima was peeling back our skulls and attaching electrodes to areas of the brain that were previously entirely unstimulated. He was showing us a new way of making and thinking about games.

I remember taking that instruction book with me while on a short shopping errand that Saturday afternoon in a calculated move to ensure I wouldn’t have to stop thinking about Metal Gear. It had its hooks in me, and once I was in that world of spies, rogue special ops groups, and shadowy conspiracies, I never wanted to leave.

We were supposed to visit our grandparents that Sunday, but stopping wasn’t an option. So we took the PlayStation with us, hooking it up to an ancient TV in their dusty basement where we could continue to save the world from nuclear disaster and learn more dubious information about genetic engineering. I know, it was a scumbag move. But in our defense, we’d just finished the torture scene, found the corpse of the real DARPA chief, and escaped a jail cell using a bottle of ketchup — neither of us were in the best head space to make positive decisions.

It was a weekend I’ll never forget. My brother and I tackled Shadow Moses together, experiencing the entire mission as a single unit. It was was a battle march, a do-or-die suicide mission to finish it in a single weekend. Even if it meant wearing out our welcome at our grandparents with multiple pleas of “just 15 more minutes!” as we pummeled Liquid Snake to death and tried to watch the hour-long ending without completely alienating the rest of the family.

So yeah, we kept the stupid manual. Call it a battle trophy, or a war memento. My brother still has it buried in some desk drawer. Besides, we did Blockbuster and the next person to rent the game a solid. When we returned the game, we taped an index card with Meryl’s codec number to the inside of the sterile white and blue plastic box. We had to crack that puzzle with brute force after we couldn’t convince our mom to drive us back out just before midnight to look at the back of the CD case on the shelf.

Kojima never accounted for us rental kids with his fourth wall shattering puzzle, but I forgive him. How could I not? He made some of my favorite memories.

The best moments I had with Sons of Liberty all happened years after the game first hit the shelves. Nowadays, I consider Sons of Liberty to be one of the most important and subversive games of all time. When we picked it up on day one though, I thought Raiden was a turd and Kojima was playing a mean spirited prank on us.

You want to talk about memories? I remember thinking “boy, I hope this is just a joke and Snake takes over again reallll soon” about a million times during the first few hours with it.

That’s not to say I didn’t like Sons of Liberty or that it was a bad game or anything, it was just frustrating. It seemed to exist only to validate every criticism of the original. That it was a bunch of nonsense for the sake of nonsense, or that it was a nice movie with some neat game bits in between. I wanted to love it, but it didn’t seem to care one way or the other for me.

Subliminally, I was picking up on the entire meaning of the game. But it’d be a long time before I could fully appreciate it.

Sons of Liberty isn’t a game you tackle in a single weekend of obsessive dead-eye play. It’s an intricate and nuanced criticism of the industry, players, and power fantasies that you revisit every few years with a scalpel and a fresh set of eyes. It’s a game that was so prescient that only now, with games like Spec Ops: The Line and Hotline Miami, are other titles even attempting the same kind of criticism it levied. It’s a game that I’ve enjoyed reading about more than I enjoyed playing. And I’ve enjoyed playing it a lot.

It would be easy to dismiss Sons of Liberty‘s message as postmodern gobbledygook, or its criticisms of Raiden, and by extension the players, as overly impressionable rubes playing pretend at being a super solider as a creator taking a shot at his audience. But I remember a time in high school when I skipped Mr. Hogarth’s class in the morning and couldn’t afford to be caught. How the blood in my veins began to pump as I saw him looming just in front of the door of one of my afternoon classes having a conversation with Mr. Jones. How I slipped seamlessly, without consciously thinking about it into STEALTH MODE, creeping up just behind him, turning with him as he turned, like I was staying just outside of the vision cone of any of Metal Gear‘s hapless guards, slipping in just past him to take my seat, no alarms activated.

The S3 plan worked better than Kojima could have dreamed. Even a pudgy high school nerd could have his own Solid Snake moment with the kind of training he provided us with.

The Substance Edition on the Xbox was where I really came to love Sons of Liberty. The VR missions more than made up for the intractable cinematics and radio conversations of the main game, finally letting me feel like I played Sons of Liberty rather than watched it. With a few years to get over the shock of playing as Raiden and absorb the message of the game’s screwy third act, I was able to enjoy the story and characters. It’s one of the few games I can think of that benefited from a remaster in a way that was more meaningful than just a graphical update.

But when it’s all said and done, I think my favorite memory of Sons of Liberty has to be slipping on bird shit and falling to my death. I don’t know why, but that’s the moment that crystallized Sons of Liberty to me.

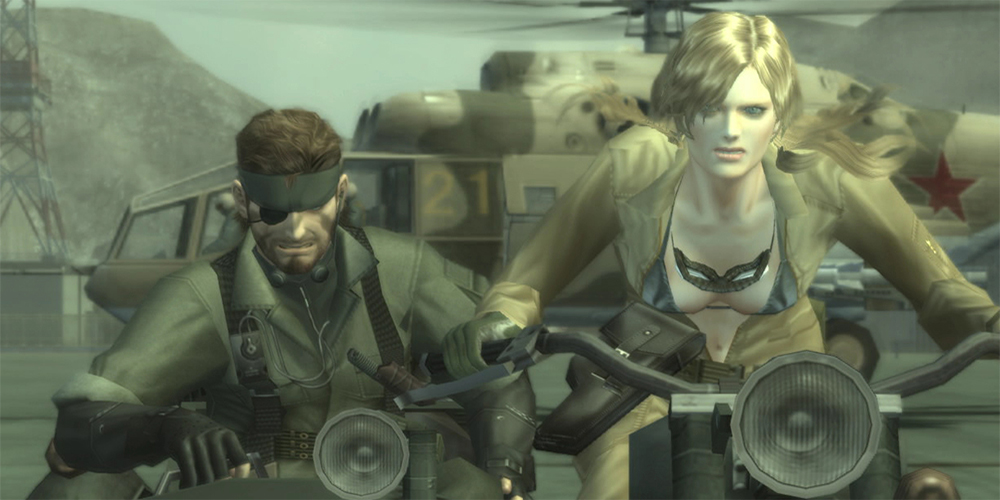

Snake Eater is one of my favorite games of all time. I’ve completed it maybe ten or so times give or take. Certainly more times than any other game I’ve ever owned. The reason I played through it so many times is simple — it kept giving me something new every time I did.

I’m not sure how many people appreciate how incredibly dense and rich Snake Eater is. If you just want to mainline the game on normal mode, stick to dependable tactics, and don’t care too much if you get spotted or have to drop a few extra people, it can be a fairly straightforward affair. If you want to dig deep though, if you want to get weird, that’s when Snake Eater really shows you what it’s really made of.

I did all of the normal things. A regular playthrough where I slit every throat I saw, blundered into enemies and tripped off alarms, and was admonished by The Sorrow who seemed very cross with the number of Russians I set on fire. I did the professional thing, where I snuck in like a shadow over Groznyj Grad, with no alarms and no surprises. Then I did the goofy stuff — theme runs where I would try and see if I could complete the game as a North Vietnamese regular (all black camo, unsilenced pistol, AK-47, grenades, and SVD only). I did runs where I would only eat fresh killed food, no Calorie Mates or insta-noodles. Runs where I tried to kill as many people indirectly as I could, to see how many I could poison with rotted food or knock off of bridges, the spirit of bad luck. Runs where I made a point of blowing up every supply shed and armory in the country.

Every time I thought I exhausted the very last bit of Snake Eater, there was just a little bit more to find. A new mechanic or trick (that of course was almost totally useless and impractical, and great), or some new weird quirk of enemy behavior (did you know you can kill The Fury with a few swipes of your knife? He even has custom dialog for it), or a new radio conversation or song I had never heard before. I played Snake Eater for years, and I’ll bet there are still one or two things left to find; Kojima’s bag of tricks never seems to end.

I still have the memory card with all of my Snake Eater saves on it, just in case I ever feel the need to get down on my belly and crawl through the weeds and marshes of Tselnoyarsk again. I had a whole library of saves, most of them right before discrete scenes or moments I knew I’d want to play again and again.

The mountain infiltration right before you rendezvous with Eva and the treacherous march back down again. Dodging KGB special operation units armed with flamethrowers, mindful of the differences in elevation and the gun emplacements littering the hill. I’ve heard The Guns of Navarone was one of the movies that inspired Kojima when working on the series, and I like to think this area is his little homage to the cliff-side raid of the movie.

I saved right before the sniper duel with The End, two different versions. One where Snake would run into his valley clad in camo greens, ready to fight a war of attrition with the legendary marksman. Another, where I assassinated the old man earlier on in the game with a single split-second crackshot (Snake Eater lets you do this because Snake Eater is a game that gives and gives every time you play it). In that version, his valley was full of Ocelot’s personal entourage of soldiers to play with. Can you slip by unnoticed while being hunted by a pack of red beret-wearing hotshots? Or maybe it would be more satisfying to unzip each of their throats one by one, or to fight them all in one glorious running battle of machine gun fire and shotgun blasts (I never really used the thing unless I was goofing around).

Of course, I saved just before the final showdown against The Boss. It’s probably the single greatest scene in the entire series and one of the best boss encounters ever designed. Sure, taking down the Shagohod was satisfying, and sneaking up on The End and forcing him to give up his special camo and rifle made you feel like a sneaky master, but this was the real test. Fighting a person with all of the same skills and tactics you’ve spent the game developing and mastering, but she’s better at them than you. After all, she invented them.

I have less personal attachment to the other games. Guns of the Patriots I had to enjoy vicariously, reading about it and watching other people play. Same with the Metal Gear Acid games. I’ve spent a good chunk of the last month catching up, reading wikis about them and watching Let’s Plays to fill in the gaps of my Metal Gear knowledge.

I think I’m ready. I’m ready to finally close the loop on this series I’ve been playing my entire life. I’m ready to experience the last chapter in this decades long story of espionage, betrayal, and hiding in cardboard boxes. I can’t wait to get into The Phantom Pain next week and see it for myself.

I’m hoping Kojima can give me a few more memories on his way out.