“Morbidcore” isn’t an established subgenre, but it’s not hard to imagine what falls into this category. These are games exploring life’s darker moments. Not for the sake of simply disturbing an audience, but instead, they’re stories communicating the more unsettling aspects of humanity — the parts we shy away from or refuse to acknowledge.

Grief, depression, trauma, and pain are all prevailing themes in these narratives, and while they don’t aim to shock, they inevitably do. Indies aren’t the only titles that attempt this, either, though they often do it best. Multimillion-dollar productions from megacorporations should have the budget to explore here, but it’s often a one-person team or a small group weaving the tales that are most impactful.

Trigger warning: don’t proceed if you’re not in a safe state of mind to read about suicide, self-harm, and rape.

On Trauma

Trauma is no stranger to many of us, and we see that reflected in indie games. Portraying that hurt is a difficult task, as trauma in its many shapes remains an incredibly personal experience. How it’s triggered, the intensity, and ways it manifests in someone’s life are unique to each individual, but we often share its weight and familiar ache.

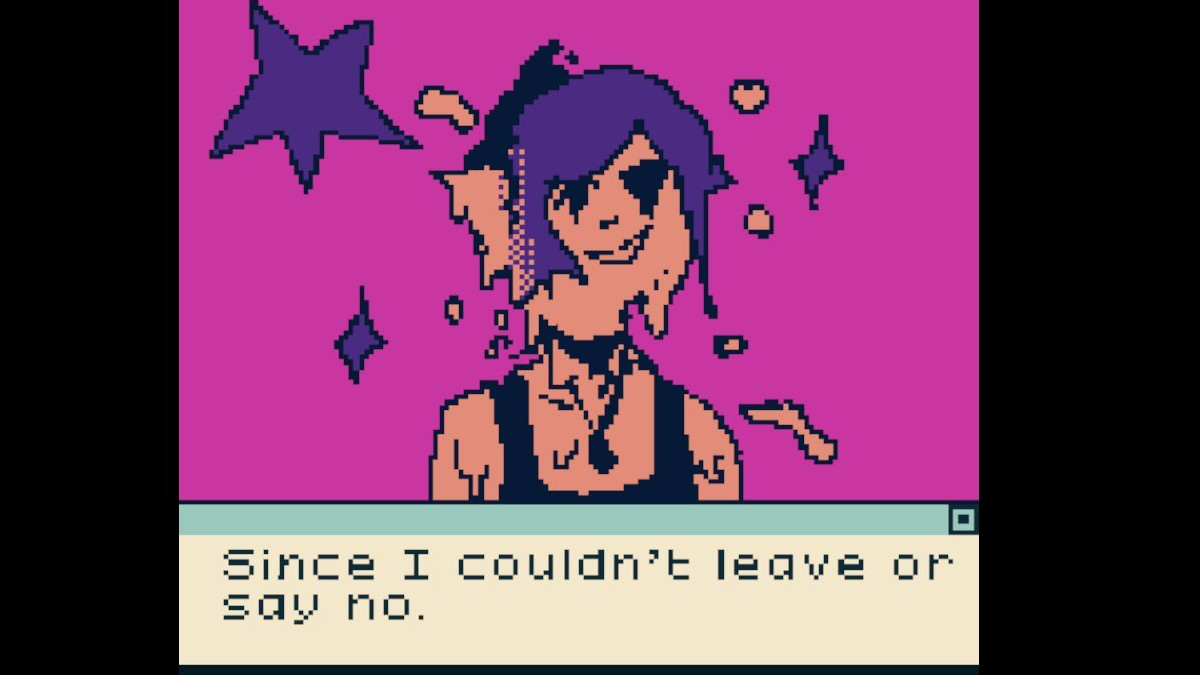

When it comes to trauma-themed games, nothing affected me quite like He Fucked the Girl Out of Me. I discovered it after reading a Zoey Handley article on the game, and with a provocative title like that, I couldn’t resist. What was I expecting? A cheeky game with some transgender themes potentially thrown in. What I got was a dark, depressing tale that’s haunted me ever since.

Without spoiling too much, the game follows the life of a trans woman bearing one-too-many heavy crosses. Drawn in by a swirl of peer pressure and desperation, she finds herself relying upon work in the sex industry. It promises her financial freedom and affection, but she is instead subjected to both subtle and exploitative behavior from predatory men. These experiences chip away at her psyche until it finally shatters, permanently changing how she relates to others.

With He Fucked the Girl Out of Me, we uncover precisely why such indies pack a more powerful punch than AAA games. When a multimillion-dollar corporation attempts to craft a game, there are economic factors to consider in addition to the complexities of blending the ideas and creative visions of an entire team. As though the situation wasn’t complex enough, there’s also the audience to consider. If you’re spending millions on an entertainment product, there’s an incentive to ensure it appeals to and parallels the sensibilities of the masses. It leaves the personal behind in favor of vague, broad strokes.

Indies often aren’t as bureaucratically fettered, allowing these games to laser focus on a singular idea from a creator, sometimes in profoundly personal ways. He Fucked the Girl Out of Me isn’t just a game, it’s an uncomfortably invasive look into the personal life story of a creator brave enough to display their shame and trauma in ways that would be entirely too visceral for most. The title makes it clear that this is a game that has no interest in mainstream acceptance. This isn’t entertainment; it’s a flash of a human soul masquerading as a Game Boy title.

With none of the limitations of the AAA industry to weigh it down, He Fucked the Girl Out of Me has the freedom to breach topics and express viewpoints seldom interrogated by the mainstream, including the thorny moral matrix of sex work. While the destigmatization of sex work is a step forward for society, it’s only half the story. With HFtGOoM, we’re reminded that in a sex industry not ruled by its workers, the prevailing norm for them globally involves desperation, trauma, and exploitation, especially for trans people.

The instinctive reaction to the indie’s harrowing portrayal of the sex industry is “shut it down.” However, spend time with it, and you’ll find it makes one of the strongest arguments for the decriminalization of the industry to not only protect sex workers but to prevent trans people from exploitation in these circumstances.

It’s a window into why indie games trigger my unease and discomfort; a level of unbridled honesty absent in the mainstream. The protagonist makes it clear that the tale is a semi-autobiographical one, expressing the pain of lived experiences. Consequently, I couldn’t shake the thought that this person’s trauma wasn’t much more than a brief afternoon gameplay session for me. I’d never wrestled with that feeling watching Aloy or Peter Parker losing loved ones.

Themes of suicide and ideation

The prior game presents scenarios that are entirely alien to my life, which gave me a bit of an emotional buffer. Actual Sunlight on the other hand… it hit a little too close to home. It centers on Evan Winter, an overweight man in his thirties who is deeply unsatisfied with his life.

You take Evan through the depressing monotony of life — doing a job he hates, returning to an empty home, rinse and repeat. He doesn’t have anything to live for, and the painful apathy slowly eats away until nihilism drives him to the roof of his apartment building. While you maintain some freedom for the majority of the game, at the end all your options are gone, and there’s only one morbid path to take.

When I first played, I was nowhere near my thirties (still not there yet) and I didn’t have a job either. Despite this, Evan’s inescapable and oppressive sense of “meh” resonated. Nothing excites him, he has no motivation to change his life, and the negative voice in his head has become a familiar soundtrack in the background.

I think it’s one of the most accurate depictions of an all-too-common pathway to suicide. The desire to stop existing doesn’t always come from a singular traumatic event. Sometimes, it’s a slow slip into a meaningless, anhedonic life. It’s a reminder that finding fulfillment requires active participation in life – it doesn’t happen automatically.

Sure, a AAA studio could create something similar, but I have a feeling that it would lack a lot of the heart that Actual Sunlight contains. The game shines through its minor and painfully personal observations. Evan’s self-loathing monologue in front of his mirror is a little too on the nose, and his disdain for the corporate world is depicted in a way that exudes authenticity. It’s not just endless kvetching about the soullessness of desk jobs – it’s a genuine cry of pain from yet another soul stuck in the 9 to 5 trap.

What are indie games doing that AAA games aren’t?

There are plenty of big-budget games that deliver a heavy, emotional punch. Who among us wasn’t moved by Red Dead Redemption 2’s ending, or wasn’t left feeling hollow at the end of The Last of Us Part 2? Despite this, I can’t think of an AAA title that has affected me as much as He Fucked the Girl out of Me or Actual Sunlight.

In an interview with Indie Game Reviewer, Actual Sunlight‘s creator, Will O’Neill, revealed that the game was made in almost complete isolation, and inspired by his own life. The result is a deeply intimate experience that might only resonate with a few, but when it does, its impact cuts deep. Or, as he explains, “I could just literally feel it emerge from that really, really personal part of myself.”

He Fucked the Girl Out of Me‘s creator, Taylor McCue, also drew from intensely personal events in her life. She created the game to escape the shame haunting her. As she explains in an interview with Game Developer, “Shame was eating into me over the course of a decade. That was making me crazy and increasingly suicidal.”

Creating the game was no easy process, and throughout its development, McCue found she was “more ashamed, more suicidal, and actually worse.”

This personal element of indie games feels like peering into someone’s diary, which can be both an enlightening and unsettling experience. The effect of this is evident in the responses McCue has gotten to her game, as she reveals she has received messages from several people sharing “explicit trauma that they shared in common” with her. Reception to O’Neill’s game has been similar, and he has received “more than one letter that starts with ‘I never write to game developers’ and which then proceeds on for hundreds or even thousands of words.”

There is something to be said about their art with a personal touch. It’s hard to make, eschewing massive teams and scope for something more intimate, vulnerable, and perhaps cathartic for too many of us. I’m often eager to sit down with my shiny, new AAA toys; flashy visuals and high production values easily capture my attention. However, when I’m searching for something that captures both the absurdity and agony of humanhood, there is no place better to turn than “morbidcore” indies.