Fourth Rock from the Sun

Mars is dead.

The International Mars Mission, a global effort to establish a self-sufficient colony on Earth’s nearest neighbor, is dead because of two idiots.

The first idiot was Anthony Krillov, an idiot whose foolish, clumsy flailing caused Mars Dome #1’s only Rare Metals Extractor to shut down, depriving the fledgling colony of needed raw materials with which to assemble electronic parts, which in turn were necessary to maintain the mission’s essential drone workforce. A cascading series of disasters stemming from the lack of maintenance led to food, oxygen, and water shortages, and before long, everyone was dead. Thanks, Anthony!

The other idiot was…myself, the dope who allowed Anthony to board the rocket from Earth in the first place, despite his having “Idiot” listed right there in his profile, all because I needed some warm bodies to help run Dome #1’s new diner. Thanks, me!

Suffice it to say, we did not survive Mars this time. Maybe next time?

Surviving Mars (PC [Reviewed], PS4, Xbox One, Mac, Linux)

Developer: Haemimont Games

Publisher: Paradox Interactive

Released: March 15, 2018

MSRP: $29.99

You’d be forgiven for assuming that a game called “Surviving Mars” might be yet another entry in the burgeoning survival genre, a Minecraft-esque recreation of Andy Weir’s The Martian, or Bohemia’s Take On Mars. You’d be wrong, but a title like that invariably conjures images of punching Mars rocks to build Mars huts and craft Mars shovels and that sort of thing.

Well, you do all of the above in Surviving Mars, except from a top-down perspective, as the game is actually a city-building and management sim from the folks that brought you the last three Tropico titles. But rather than playing a developing-world dictator, players this time step into the environment-sealed boots of a Martian colonial administrator, tasked with establishing humanity’s first extraplanetary settlement. For that to happen, of course, survival is a must.

The “surviving” part of the title refers to the fact that just not dying on Mars is a major challenge. The planet has no breathable atmosphere, no running water, no directly arable land, and limited surface resources. Water, oxygen, living space, and all of the basic infrastructure of the colony must be laid down before a human even steps foot on the surface. That much is true from what scientists have said about the challenges facing real-life Martian colonization plans, and the same is largely true here.

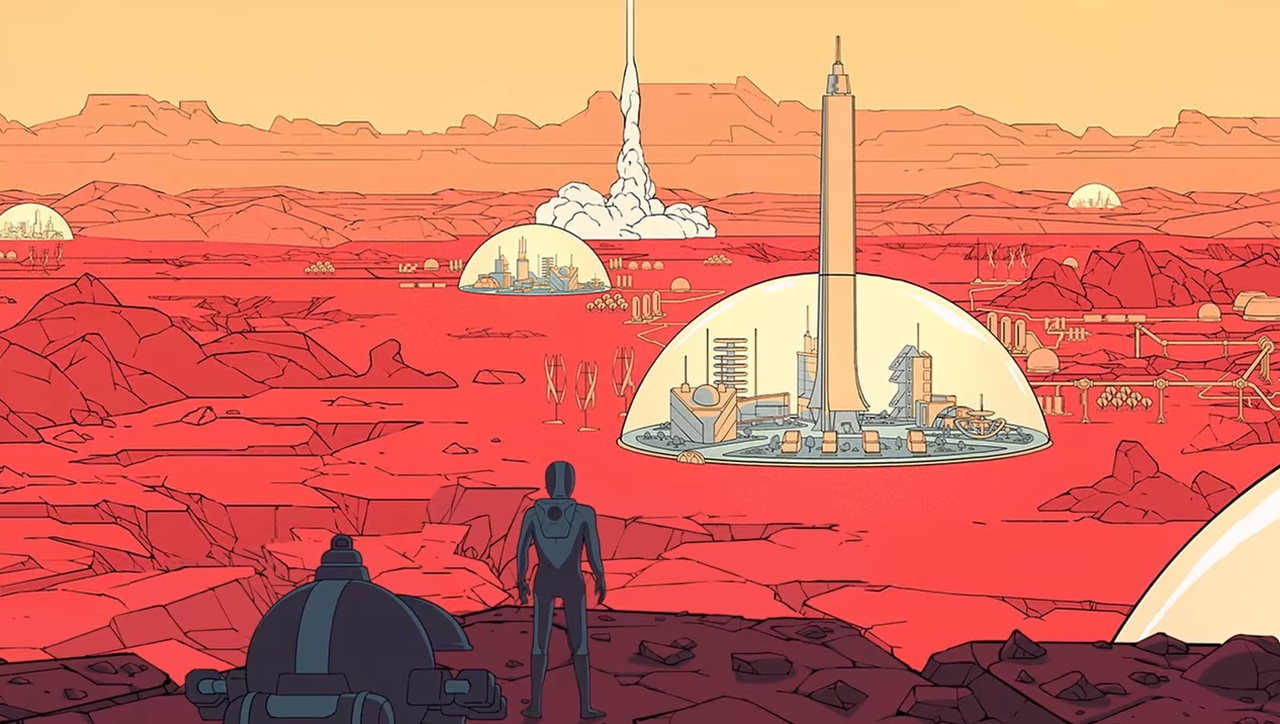

As such, the game’s opening hours – usually the first two to five or so depending on the difficulty level – are spent in control of a convenient, remote-control drone army. Paired to trundling rovers or static drone hub buildings (or in some cases, the landing rocket itself), the drones must harvest and stockpile resources, lay down grids of power lines and life support piping, and build Surviving Mars’ trademark habitat domes, transparent hemispheres seemingly taken straight from 1960s science magazine covers or pulp novel illustrations.

The challenges shift once the passenger rockets ferry the Red Planet’s first colonists to the surface. Where once the priority was putting down roots (and making sure a surplus of water and air was in storage), Surviving Mars moves to a settler mode of living as the colonists establish farms or hydroponics bays to grow food, operate extractors to bring in raw materials, or man factories to turn those materials into advanced components like electronics, polymers, and machine parts.

Those advanced components are key, as they’re often critical to building and maintaining all but the most basic structures. Eventually finding a reliable source for them is crucial to sustaining the colony, lest it be completely dependent on cargo rocket deliveries from Earth. These deliveries play a key role in the early game, as advanced materials and even some key buildings (like Drone Hubs or parts factories) can’t be built natively on Mars without a good deal of technology research.

Summoning those rocket deliveries can cost money and time, and can’t be done repeatedly, since the rockets need to be refueled from the colony’s own precious fuel supply before being sent back. In the mid- and late-game, though, rockets can be key sources of additional funding, as the ones on-planet can be used to export rare metals to Earth for an infusion of cash. That said, cash isn’t really that important in Surviving Mars, with “Mission Funding” mainly used to order up rocket deliveries and to accelerate the pace of technology research via outsourcing. Besides those two functions, Martian colonies are refreshingly free of the need to scrape for money, loans, or tax revenue that can permeate other management sims. This might be one of the few games I’ve played where the most important resources are actual resources and not currency.

It’s clear that there are lots of things to do from the outset in any given Surviving Mars run, and players will find themselves scrambling to keep up. Even meeting the colonists’ basic needs isn’t a guarantee, though, as hazards and the luck of the randomized terrain engine can leave a colony site far away from one key resource or another.

But all of this work to keep alive takes its toll, and would-be Martians have needs beyond the next meal or breath of air. Such needs can range from a desire for social interaction, a love of trees and grass, a preference for solitude, or even a spot of good ol’ “gaming.” These needs are measured as “comfort,” and can usually be met by building and staffing specific in-dome structures – like diners to facilitate socializing or parks to add some earthly scenery – but building space is limited in all but the biggest domes, so players will have to balance necessary structures like living quarters and industrial facilities with creature comforts.

Things get even more complicated when taking into account various positive and negative traits every colonist has. Geniuses speed up technology research by their very presence. Saints improve the morale of every religious person in the dome. Sexy people are more likely to have kids, and Nerds gain a morale boost whenever a research project completes. Idiots can randomly disable a structure, requiring a direct drone intervention to fix. Damn you, Anthony!

All this can inform a player’s approach to building and populating the habitation domes, as maximizing space to leverage the traits and preferences of a given dome’s residents is key. The various colonist specialties also skew different ways with regard to preferred comfort. For example, botanists, who work best assigned to food production, often like a taste of luxury after a hard day harvesting crops, so shops and luxury goods can keep them happy. But security personnel and medics need to stay fit, so gyms and parks work for them. But does their dome have enough space – or the colony enough power, water, and oxygen – to build and maintain all that and more?

This balancing act of resources and upkeep informs virtually every aspect of Surviving Mars, and the additional hook – the central idea that everyone pretty much dies if one of these resources should run out for even a short time – lends the consideration a special kind of weight absent from an Earth-bound title. That kind of survival tension and focus on small-scale communities over larger, vision-driven urban planning, brings to mind 2014’s Banished, a game that attempted to simulate the harsh conditions of carving a village out of the medieval wilderness before winter set in.

Colonies will naturally gravitate to specialization, and the game obliges, making it easy to set up specific domes as, say, farm-filled agricultural areas, or mining-centric domes placed near resource extractors, each equipped with facilities tailored to keeping the population in the pink. This allows domes to supply each other in a more intimate, organic, take on the way 2013’s SimCity posited a vision of distinct cities all feeding progress for a larger region. Even incoming colonists can be sorted into different domes based on desirable traits or specializations, so that all the botanists can go here to run the farms and all the geologists can go there to run the mines. Lord help you if a random disaster like a cold wave or dust storm disables the supply network, though. This has happened to me, and the results were ugly.

Well, “ugly” in the philosophical sense, because the game’s a looker. Bearing a clean, retro-future aesthetic, Surviving Mars trades in rounded domes, bright colors that pop well against a somewhat dull (if admittedly realistic) desert environs, and an unusual hex-based grid scheme. The hexes are unique, though they tend to make placing orderly right-angle grids of power and life-support lines a bit fiddly. The game even includes a native Photo Mode for putting together cool screenshots of the settlements. Aurally, Surviving Mars can seem rather quiet…at least until one finds the in-game radio stations, complete with DJs and distinct selections of music. I for one preferred the funny commercials to be found on Free Earth Radio, but Red Frontier’s country-inflected playlist made for relaxing construction sprees.

There’s more to learn that I haven’t gotten into detail about, like scanning sectors on the map for resource deposits, automating supply lines with AI-controlled shuttles, or even the way every run feels different thanks to the way the game randomizes its research tier list. And I haven’t even gotten into the narrative.

Such as it is, Surviving Mars can also have a story of sorts, depending on one’s choices when starting a new game. “Mysteries” are narrative arcs, ranging from classical alien contact to something that seems to resemble a sci-fi infused cosmic horror tale. The stories unfold slowly, through brief text and voice interludes that can be triggered by exploration or hitting certain milestones in colony development. Though they made their presence known a bit late into the game for my preference, the mysteries I played through made for a welcome seasoning of drama in a game that can, at times, feel a bit sterile.

That sterility I mentioned is one of the minor gripes I have with Surviving Mars, in that despite its ostensible emphasis on keeping up with the needs of a growing community, there’s little humanity in the game. Colonists tend to be reduced to simple summaries of their traits and specialties, and the scale of the settlements means that there’s no efficient way to go full-on into personal micromanagement, as the somewhat Sims-like emphasis on characters would encourage. The game has no wordy or personable adviser characters, either, nor rival factions to deal with and make into enemies. It’s just you, your colonists, and the planet, for the most part. The mysteries tend to take care of the grand narrative sweep, but I would’ve appreciated that the spaces between were filled with just a bit more drama and personality than the routine of building, expanding, and maintaining.

Besides that, the game’s sense of time feels a bit off. For gameplay reasons, Surviving Mars simulates a day-night cycle based on Martian “Sols”, days roughly as long as Earth days. This adds a consideration to power generation, since cheap solar panels don’t work at night, but at the same time, entire generations of colonists can be born, live, and die, in the course of a few Martian weeks. By “Sol 40” of my Martian odyssey, several of the colonists I started the game with had already aged out of the workforce. It’s a cosmetic thing that ultimately has little gameplay impact, but this cognitive dissonance with regard to time can break immersion.

My gripes aside, Surviving Mars might be the most fun I’ve had with a city-building game since SimCity 2000, and Haemimont has accomplished this feat by drilling down into the details, and zooming in on the kinds of small-scale community-building that I’d always felt the that city-builders with a grander scope lacked. The promise of robust modding support from launch could also ensure that the game has legs, or even that some of my complaints could be addressed by fans soon after they get their hands on the toolkit.

I’ll just have to make sure to keep the idiots out of the machinery next time.

[This review is based on a retail version of the game provided by the publisher.]