Learn collective storytelling, Robit by bit

Tabletop role-playing has survived all these years, through the advent of video games and the resurgence of board games starting in the 1990s. One reason it’s still around is that it provides an experience those other media don’t. It gives players a venue to tell a story as a group, to think laterally, and to play off each other’s ideas.

One of the biggest barrier to entry into role-playing is the need for a dungeon/game master. And it’s not just a DM the group needs for a successful campaign, but a good one. One who will provide interesting situations, force difficult decisions, and allow players the freedom to deviate from the pre-written path.

Robit Riddle is trying to address both of these to an extent. Billed as a storytelling game, it serves up the skeleton of the story, but leaves the details to the dice and the imagination.

Robit Riddle

Designer: Kevin Craine

Publisher: Baba Geek Games

Players: 1 – 6

Play Time: 30 minutes

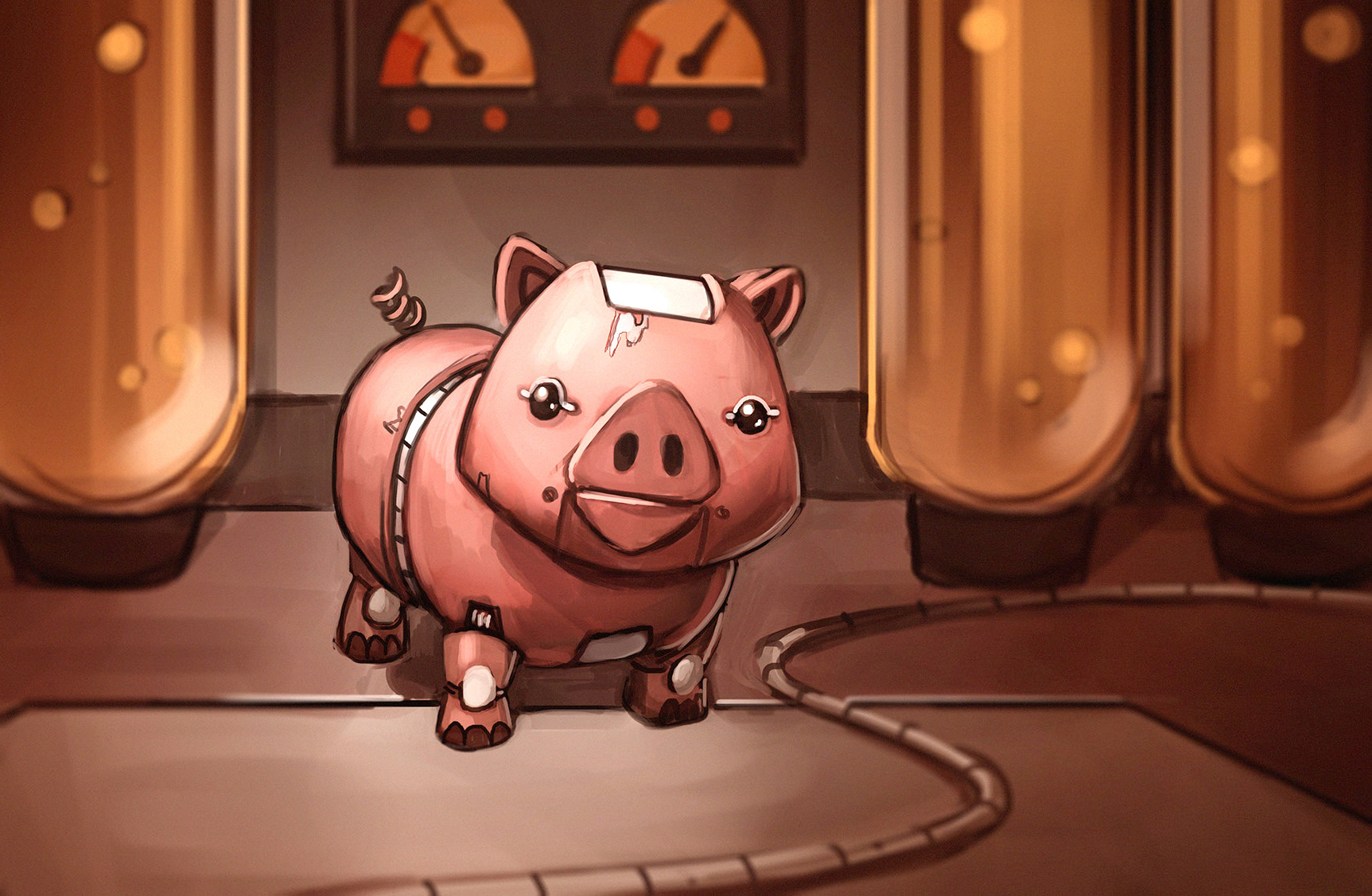

In the world of Robit Riddle, everybody is a robot. Not only are the sapient protagonists robots, but their pets are all mechanized animals called “Robits.” (There is an especially adorable robot pig. I want it.) Problem is, one day all the Robits disappeared and nobody knows why. It’s up to the plucky adventurers to figure it out and bring them home.

Taking on the role of the DM is a Choose Your Own Adventure-style book. Though it lacks the ability to react organically like a human would, it does allow for a bit of leeway in player decisions. There are flat decisions to make, taking players down one path or another, but there are also branches depending on skill tests that can be fudged with a bit of creative thinking.

In the example given by designer (and legendary Destructoid community member) Kevin Craine, he needed four successes on four dice to open a door to explore an area further. Kevin rolled two successes, but then made up the difference with special character abilities called story cues. One character had mechanical skill, but that’s not enough on its own to break through. Players are encouraged to examine the fully illustrated scenes and describe in a few sentences exactly how that expertise would help in the situation.

Then, since we were still down one success, another player had to lend a hand, use one of his own skills, and build on the ideas the first set as a foundation. Our example was a simple one: the player noticed a wall panel near the door, and used his mechanical intuition to surmise that if the party could get that panel open, it could access the door. The second player used his physical strength to pry it open, and it ended up as a success. That whole scene was set by the single still image of the room — there’s nothing in the book explicitly tying the door to the panel.

As a reward for getting through the door, the active player was awarded with a new story cue ability. The old one was spent in the previous trial, so each character’s skill set will evolve over the course of the game. Coming across a similar situation in the future might play out completely differently, depending on who’s doing the talking and which cards he has access to at the time.

Sure, it’s no replacement for a real live DM, but Robit Riddle‘s ability to be freestyled like that is impressive. As an introduction to group storytelling, it provides just enough of a jumping off point to get beginners into the improvisational gaming mindset.

The subject matter and difficulty skews young, which could be a turnoff to some. Craine wanted to design a game that parents could play with their children. Robit Riddle‘s Kickstarter campaign was a decent success, so it looks like there’s a market for gamers with sons, daughters, nieces, nephews, or other little ones who could stand to spend more time using their imaginations to solve problems.