Retro Rampage

Being someone who never really stopped playing games after they reached their expiry date, I spend a lot of time thinking about the flow and evolution of game design. Why, after some successful genres reach a certain age, did the industry just collectively seem to move on? As with any art form, trends constantly emerge in the medium of video games. As is also common, we eventually circle back to the ones we fondly remember, and video games seem to be the most literal when it comes to that. It wasn’t enough for the side-scroller to reach a resurgence; the pixel-prominent visuals had to come with it.

Yet, we also live in an age where we are protective of our art. The internet has ensured that you can obscure, but you can’t destroy. If I’m ever in the mood for Roller Coaster Tycoon, it’s still within reach. How, then, does a retro-inspired game become successful? In a world where I can play Mega Man on modern consoles, what entices me to play Shovel Knight?

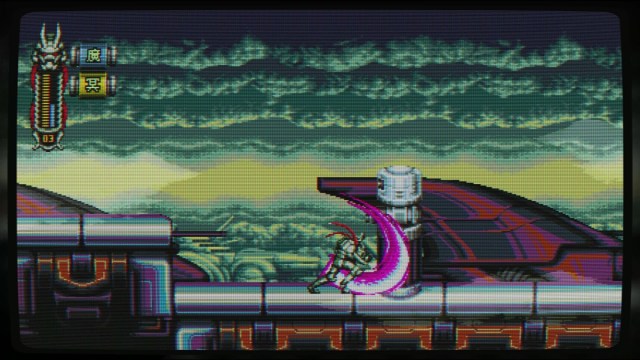

Good people to ask would be JoyMasher, creators of Oniken, Odallus, Blazing Chrome, and the recently released Vengeful Guardian: Moonrider. So, I did. Danilo Dias and Thais Weiller at JoyMasher took the time to talk to me about their approach to the retro formula.

Nintendo hard

A big obstacle for a lot of people when it comes to playing games from before the ‘90s is their difficulty. A descriptor that got thrown around a lot a couple of decades ago was “Nintendo hard,” and while I don’t hear that as often anymore, there’s still the perception that primordial games were more difficult. I’m not disputing that. Lives and continues aren’t seen as often, checkpoints are commonplace, and difficulty settings that let you choose your challenge are more widespread. I’m not complaining. I like a bit of challenge, but games were often made unfair to eat quarters and dissuade rentals; things that aren’t concerns anymore.

However, the lives system is still used today, primarily in retro-inspired games. “There are the types of retro games that tend to be difficult for the sake of getting quarters. This created some kind of culture that even console games should be difficult. This is kind of cool in some ways because you don’t need a lot of material to entertain for a long time,” Danilo explains.

A good example of this is Contra, or just about any run-and-gun shooter. Contra on NES can be completed in about a half-hour if you know what you’re doing, but because of its limited lives and continues, you’re not likely to beat it on your first try. You need to play it again and again, learning boss patterns and enemy locations, before you’ll finally be able to topple it.

To explain one of the benefits of this, Danilo brought up Elden Ring. “It’s super-long and super-difficult. It’s difficult for me, as an adult, to spend so much time in a game. But when you have a short game that you can play and replay and replay to get off a stage, the difficulty is there, but you become good as your replay. It’s designed in a way that I want to put in some of our games, so it’s difficult without being cheap or unfair.”

The skill gap

I asked Danilo what his opinion was on what game has the perfect difficulty. “Super Mario Bros. 3 was difficult, but not impossible, and most kids during that time were able to beat it. It’s fun, but you get it really fast.” He also brought up Mega Man 2 as having the right balance of challenge and fun.

One thing that I’ve personally wondered about is how a developer can gauge difficulty when creating their game. Playing through a challenge you created yourself isn’t the same experience as having someone new try it for the first time.

Thais described that for Joymasher, “We generally try to aim at retro gamers, but we end up also hitting the other players. Some time ago, some students tested Moonrider. The players that they tried with were basically new players who didn’t have experience with retro games. We can’t pretend that we aren’t retro players. So we asked them to try the difficulty and try to assess if the difficulty was too much for this kind of player. Both times (because there were two different groups), the results were that they found the game difficult but fun and wanted to continue playing after the test was over.”

Danilo added that, “For younger players, retro games are a challenge, but they’re easier to understand. They’re not as complicated as something like Dark Souls which has a lot of buttons and mechanics.

Personally, I found Joymasher’s Vengeful Guardian: Moonrider a bit on the easier side, but I have beefy thumbs honed by decades of pressing buttons real fast. Even still, I can point to games from the time period it emulates on the same level in terms of challenge. It fits with the era, it just avoids the quarter-sucking, rental-frustrating designs that were so common.

Knowing your limitations

An important feature for me when it comes to retro-inspired games is aesthetic, and JoyMasher is one of the best at adhering to the look of previous generations. It’s more than just pixel art. Pixel art is a valid aesthetic choice in games like Stardew Valley, but I have more respect for developers that pull it off while being mindful of limited color palettes, animation, and tech restraints.

“Pixel art is a limitation as an artist, but also I will try to emulate the limitations of the hardware,” Danilo explained. This approach is also common to the soundtrack. He clarified that Vengeful Guardian: Moonrider doesn’t stick to the 6-channel FM-synth of the Genesis hardware, instead sounding more like a CD based system, such as the PC-Engine CD or Sega CD. The Japanese voice samples used are intended to harken back to Castlevania: Rondo of Blood when some of the bosses would taunt you.

The attitude toward pixel art, in general, has shifted substantially in the past decade. In the days of Xbox Live Arcade and Mega Man 9, anything pixel art was typically labeled with the blanket descriptor “8-bit,” and sometimes developers would be accused of pandering to nostalgia. Now, it’s more often seen as what it is; an aesthetic choice. A prevalent one, sure, but no more prevalent than cell-shading or photo-realism.

Aesthetic adhesive

It seems to be mostly a balancing act between trying to do something different while adhering to a previous era. It’s a method that is largely unique to video games, as storytelling mediums rarely reach back to the limitations of the past, unless it’s simply to make fun of them. Game design hasn’t necessarily gotten better over the years. While we’ve ditched some of the mistakes that were commonplace decades ago, there are plenty of new annoyances that have taken their place. Trends come and go, and what was popular a few years ago may have fallen out of fashion. Video games are less like a ball rolling down a hill and more like a sloshing cauldron of stew.

JoyMasher is very successful in that balancing act. Each one of their games has been worth playing, while still evoking eras gone by. Better yet, they do it while keeping to the limitations of the hardware. Whether or not games like Blazing Chrome and Vengeful Guardian: Moonrider go down in the books as classics is going to depend on the person playing them, but they can at least be pointed to as retro-inspiration done right.