A few weeks ago I tackled the issue of why videogame endings are so hard to execute effectively. So as not to be a Negative Nancy incapable of pointing out excellence in videogaming narratives, the following is a list, however brief, of videogame endings that don’t suck.

While not complete by any means, this list was compiled with the help of the loyal posters of the Destructoid forums and will (hopefully) further clarify the points made in the first article.

Anyway, time’s a-wasting: hit the jump to hear about tragic inhumanity, clever cliffhangers, and tortured heroes – with video evidence for each ending, of course.

It should also go without saying that this article will be spoileriffic.

Fallout

I was going to write a big fat diatribe about how Fallout contains one of the single best videogame endings of all time through its use of dark, ironic tragedy, but TheRob91 put it better than I could have:

The ending for Fallout was my favorite ending. Its not really a story driven game, in fact its one of the least linear games I can think of, but the endings are great. Each of them shows the horror that the world as turned into because of the fallout, and what choices it makes people make. The entire point of the game is you leaving a fallout shelter to go get a water chip that your vault needs and then risking your neck to eliminate a growing mutant force and their leader, “The Master” before he transforms everyone into genetic mutants and basically eliminates the human race. Once this has been accomplished the final scene is that of the main character returning to the vault which he has saved. Unfortunately, because of all of his time in the desert he was not allowed back into the Vault due to fear of him being altered by the radiation in the wastelands.

This ending is great in a few ways. It creates an emphatic exclamation point to the main point of the game – that the world humans live in after the fallout is a very harsh and unforgiving place. You have risked your life to save everyone else, a perfect example of a good role model, yet for this act of altruism you are sentenced to live in the way that you were so fervently trying to prevent your fellow vault members from being sucked into. This is also further expanding the hardships that a truly heroic person must experience. Its not a cheap “try real hard then you’ll have a happy ending” type of atmosphere. This shows the excruciatingly severe consequences that can come from a realistic world, rather than a world of hugs and kisses.

And, of course, it is good for the developer as well, as even though it is a “sad” ending, it is not merely done by killing off the main character. Because of the ending leaving the main character alive it allows for sequels that still have to do with the main character.

And, although it has multiple endings, it’s pretty rough on the hero when the best ending is that the protagonist is sent into exile in a radioactive land. Each of the endings reinforces the main “point” of the game, that the nuclear fallout has created an unforgiving world that no human being would want to be part of.

Metal Gear Solid 3

Though I friggin’ hate the third MGS game with an unparalleled rage, many pointed out that it had the best ending in the series. Leviathan called it “poignant,” kevvo called it “totally fulfill[ing],” and tehdopefish called it “wtf was going on in mgs2”.

Essentially, Big Boss gets screwed over in literally every conceivable way. Dude loses an eye, is forced to kill his mentor and mother figure, gets screwed over by a woman he fought to protect, and eventually finds out that the entire operation was basically one big, selfish double-cross by the

Given that Big Boss is the main bad guy in the first two Metal Gear games, it’s refreshing to see his troubles from a different angle. Rather than being a one-dimensional terrorist baddie, one would be hard-pressed to blame Big Boss for his terrorist actions after seeing how the

While I cannot possibly understate my irritation at essentially every aspect of MGS3, even I have to admit that the finale is pretty well done, in hindsight.

God of War

All things considered, God of War didn’t really need a story. It could have floated by solely on its hyperviolent action and incredible level design, and nobody would have complained – which makes it all the more wonderful that God of War has a truly great storyline. The player is told at the beginning of the game that Kratos will finish the story by hurling himself off a great cliff, having been unable to find peace from his inner demons. Once the player finally reaches this point, the game does what all works of fiction that start with the ending ought to do: show you exactly what was promised, but change it up to make it surprising and interesting.

The ending of God of War is effective in that it delivers on what was telegraphed at the beginning of the game (Kratos does indeed attempt suicide), but the context is changed enough to make the ending worth the hours and hours of gameplay the player invested in order to see it. For an example of this sort of ending not working correctly, watch the TV show Heroes. Or better yet, don’t.

What makes the ending even better is the fact that – as was the case with MGS3 – the hero is technically rewarded, but in reality remains a suffering, tortured soul. This serves more than just a narrative purpose, obviously (in order for future sequels to make sense, Kratos still has to be a mean, angry bastard), but it still gives the game a satisfying denouement. Kratos has “won,” but the game stays true to its original tone and refuses to give this brutal, antiheroic killer any solace from his past transgressions.

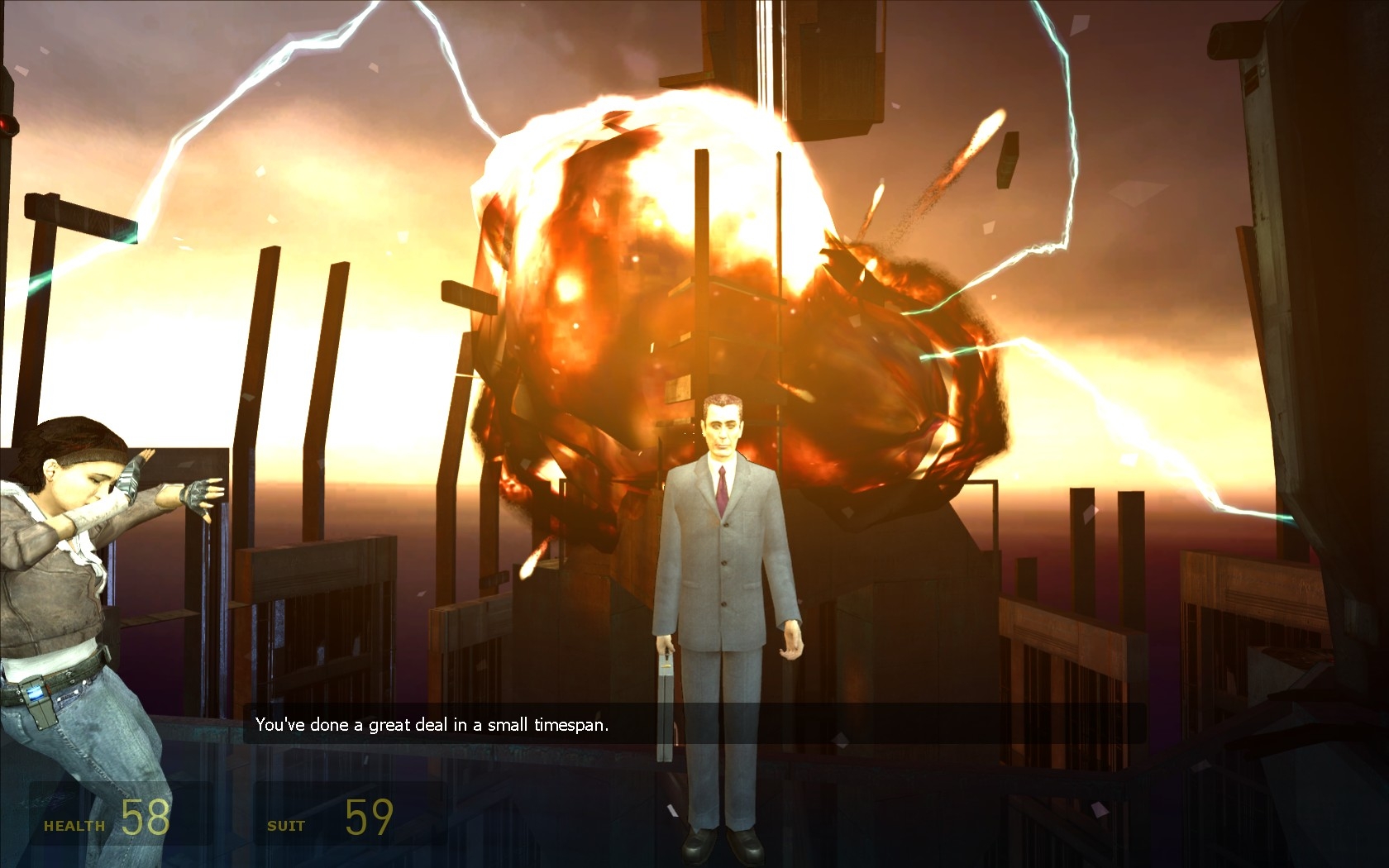

Half-Life 2

Don’t get me wrong, the ending to the original Half-Life is great (Hobson’s choice ftw), but it doesn’t hold a candle to Half-Life 2’s conclusion. It’s a cliffhanger ending, which still leaves many gamers understandably irked, but what remains most important is this: it’s a cliffhanger ending done well.

This isn’t Halo 2: Gordon Freeman doesn’t get all the way to his ultimate goal, promise to “finish the fight,” and then disappear entirely for a few years. Half-Life 2 delivers the goods: the superpowered gravity gun makes for some of the greatest gameplay moments I’ve ever experienced, and the de facto boss fight where Gordon attempts to prevent Breen from escaping was suitably climactic. But what makes Half-Life 2 so very special is that when it abruptly ends and deprives the player of a satisfying epilogue, it happens for a reason.

It makes perfect sense that the G-Man would extract Gordon from City 17 at that exact moment in time: Gordon is a tool, and once he has served his purpose, the G-Man effectively and immediately returns him to his toolbox. I felt cheated, but not by Valve: instead, I felt a great deal of ire toward the G-Man, and everything he stood for. Narratively, it wouldn’t make sense for the G-Man to allow Gordon what he (and the player) so dearly desire: more time with Alyx, a chance to help the resistance rebuild, and so on. The sudden removal of Gordon from the scene makes perfect narrative sense, but also poses interesting questions.

And again, unlike Halo 2, the question is not “when the hell am I going to get to kill the rest of the bad guys,” but “what happens to the characters?” Since the plot is technically finished (the Combine are pretty much done for, as is Breen), the only real questions left unanswered involve characters the player has empathized with throughout the agme. The fates of Alyx, Dog, Eli, and Kleiner remain unknown, and this is where the real tragedy of Half-Life 2’s ending comes into play. The player has come to care about Alyx and Dog, yet considering the final image of the Citadel exploding, it seems more than likely that Alyx might be killed in the resulting blast. It leaves the player in suspense, without making it feel like the developers just up and decided to end the game – in other words, it’s the exact way a cliffhanger should be executed.

Shadow of the Colossus

Digial52 called it “the first and only ending to make me feel sad for a video game character,” and Tectonic says that “This the only game that made me feel morally responsible for the outcome – that because of my need to progress such beauty was destroyed and a demon was almost unleashed on the world.” DinnertimeNinja cites it as “a good example of a sad, yet hopeful, ending.”

Personally, I have to censor myself from gushing too much over the ending to SotC: not because I’m worried about spoiling it for those who haven’t played it yet, but because it seems I gush over SotC at least once a week these days. Still, the ending of Shadow of the Colossus bears mention on a list of great endings; not only does it successfully encapsulate the ambiguous nature of the game that preceded it, but it also remains extremely effective and at least partially interactive.

As with Half-Life 2, I know of many people who were irritated with the ending to SotC. They wanted it to explain everything, which may or may not say more about the people who didn’t like the ending than the ending itself. Just putting that out there.

Anyway, the ending to Shadow is not one for those who like their narrative spoon-fed to them. Though the mysterious riders who pursue the protagonist all throughout the game finally catch up with him, and though the ultimate result of killing 16 colossi is finally revealed, no more is said than is necessary. The true identity of the girl the hero tries to save is never revealed, the origin of the colossi and the imprisoned god are never explained, and the game’s possible connection to Ico isn’t fully spelled out, which led to one astonishingly stupid forum debate I engaged in, wherein someone tried to tell me that the whole “child with horns” thing was merely an aesthetic motif rather than a thematic one, a la the Chocobos and Cacutars of the Final Fantasy. But ambiguity aside, the ending satisfies in a wholly tragic way: not only does the player have to watch his character complete the gradual transformation from man to beast that started early on in the game, but the player actually controls it. The ending, as justinroman pointed out, “uses gameplay to make the emotional point rather than just a cutscene.” The player actively takes the reins of a colossus, if only for a few moments, before the protagonist is slowly sucked into a vortex as he tries to get one last look, one last touch, of the woman he fought so hard to save. This sequence, too, is fully playable, which absolutely adds to the tragedy: “if only I could find a way to jump ahead and fight the force of the vortex, maybe I could get to her one last time,” the player thinks.

Sadly, this turns out not to be the case. As commenter SLiFE put it: “While you can’t change your fate, having some control during the ending was great, and ultimately more satisfying than if you had just been watching.” Yet all this darkness and tragedy is tempered with a final moment of hope: Agro, the hero’s horse, turns out to be alive, and the hero himself has been turned into a tiny horned child – ostensibly the first of a new race that would one day come to be loathed and despised by a prejudiced world by the time Ico begins.

In other words, horned children aren’t like fucking Chocobos.

Planescape: Torment

Forumite yaesir considers it “one of those endings that you never forget…it is fulfilling and makes it impossible to have a sequel.”

In the last article, I said that multiple endings are difficult to execute effectively. The reason I said “difficult” and not “impossible” is because of games like Planescape: Torment. For all the nonlinearity and multiple conclusions the game has to offer, there is one thing in common to every playthrough of the game: in the end, the protagonist must die. It’d be too much trouble to go into why this makes so much sense in the context of the game, but suffice it to say that The Nameless One made himself immortal to avoid going to hell, and that his immortality could essentially destroy the universe.

Given that the main themes in the game are fate and futility, all roads end in essentially the same way: based on how the player acts and who he befriends along the way his death may be much more comforting, or infinitely more tragic (imagine watching every single one of your companions die, violently, just for befriending you). Planescape’s nonlinearity never compromises its storytelling: it has a particular story it wants to tell, very specific themes it wants to develop, and though the player can complete the game in a half-dozen different ways, the story is always engrossing, satisfying, and utterly tragic.

Hitman: Blood Money

When I think of the ending to Hitman: Blood Money, the things that sticks out most notably in my mind are the reporter and the priest. Yeah, there’s the fun pseudo-ending where the credits begin to roll, and the big gunfight, and the ability to take revenge on the government guy who had been tracking 47 down since the beginning of the game, but what affected me most, and what still makes me feel somewhat uncomfortable, was the presence of the reporter and the priest.

Basically, the entire story of Blood Money is told through flashback, as a reporter talks to a handicapped government agent about all of 47’s numerous murders. The reporter is simply curious, and wishes to uncover what he believes to be a major conspiracy – considering the government guy is something of a douchebag, the reporter quickly became a character I sort of cared about.

Until that last gunfight, anyway. At 47’s “funeral,” he is given what basically amounts to a “wake the eff up” potion and suddenly comes to life, blowing away an entire cadre of FBI agents right before killing the government man who set him up in the first place. Bing, bang, boom. Done, right?

Wrong. Because while 47 may have killed every character who outright attempted to murder him, two characters still remain alive: the reporter, and the priest who presided over the funeral. They’re innocents, and therefore would not usually be killed (most every mark in a Hitman game is a criminal in some way or another). Yet the game isn’t over. The credits haven’t rolled. The priest and reporter bang on the church gates, trying as hard as they can to get out. The first time I played through the ending, I stood still and waited for them to escape – it isn’t their fault they were at the funeral: the reporter just wanted a story and the priest was just doing his job. Then I realize it: I have to kill the priest and reporter in order to end the game. Since they’ve seen 47’s face, they are a liability, and 47 would know that. Begrudgingly and uncomfortably, I blew away both priest and reporter, and was treated to a more or less irrelevant final cutscene.

Killing these two innocents was uncomfortable and awkward, which is exactly what it was supposed to be. The first few Hitman games made 47 out to be some sort of hero, as he protected prostitutes and priests and what-have-you — Blood Money carries no such sentimentality. Regardless of how many trailers for the upcoming film decide to call 47 a heroic exterminator of evil, he is a killer, and operates the way any efficient killer would: the player must kill the two innocents because it’s exactly what 47 would do. In a sense, the player is held responsible for his actions: blowing away guards and criminals level after level is fun in a totally inconsequential sort of way, but what happens when the player is forced to look two innocent people in the eye and kill them solely out of self-preservation? In choosing this ending, Eidos wisely opted not to romanticize the life of a hitman, as other videogames are wont to do: 47 is an amoral killer, and the game truly thrusts this in your face in its final moments. It’s a thought-provoking, narratively satisfying, and emotionally affecting way to end the story.

Still, I have to agree with UniversalTarget, who calls the final gunfight (scored to Ave Maria) “pretty darn cool.”

Killer 7

Says forumite Hiltz:

The mystery of who and what the Killer7 are along with the sad reality of Garcian Smith’s fate was presented in such a cool and stylish way that was truly satisfying, original and memorable. It’s a rare thing to experience in the gaming industry that doesn’t seem to give enough praise to creative, open-ended and thought-provoking story telling.

What made the ending of the story even more entertaining was when the player realizes before Garcian Smith does what is inside his briefcase as the powerful and emotionally uplifting ending song “Dissociative Identity” continues to play on as the credits begin to roll by against the dark night on top of the Hotel Union.

In addition, the game’s final ending during Chapter Lion was spectacular. The next showdown in the future between Harman Smith and Kun Lan signaled the beginning of a new chess game with the adrenaline-pumping “Reenact” song to put an end to this great game

Having never worked up the courage to finish Killer 7, I have absolutely no idea what he’s talking about — but there you have it.

Bad Dudes

If you’ve watched the video, what more needs to be said? After saving the President from a gang of ninjas (if that sentence doesn’t make you grow an extra testicle out of sheer manliness, read it again until it does), he invites you to share a burger with him, and laughs in a way that no uncybernetic human being could ever possibly laugh: “Ha! Ha! Ha!”

Then, of course, it cuts to the president, standing in front of the White House, eating a burger. Evidently, the game’s protagonist is such a Bad Dude that he refuses to share one with the Commander-in-Chief, and instead chooses to stand with his arms solemnly crossed, like a true badass.

No one will ever make a better videogame ending. Ever.

For more endings adored by the Destructoid community, check out the official thread in our forums; whilst there, stand in awe as BlackDove spends two pages recounting all the different multiple endings to three of his favorite games. I left out many, many of the endings mentioned in the thread from this article, mostly due to either my lack of personal experience with the ending in question (Chrono Trigger), or a lack of user explanation. That, or I’m just a dickhead and I didn’t notice your post. I can’t stress enough the fact that this list is by no means comprehensive, or complete.

Either way, you can always use the comments to elaborate on your favorite endings, and why you dig them so much.