Everywhere the sun touches

Digital worlds becoming open playgrounds was sort of a foregone conclusion in the world of video games. Some of the earliest games were attempts to translate Dungeons and Dragons to a digital format, and there are no walls in tabletop roleplaying games. Well, I mean, there are if the dungeon master says there are, but the fact is that they’re restrictions that the imagination can build beyond.

Yet, despite having the only defining factor being “a roamable map,” there have been many distinct approaches to this. The open world of Grand Theft Auto III is rather dissimilar to the one in the Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Not simply because one is a city and another is a field, but because their usage of the concept is wildly different.

The sub-genre, as a whole, has its pros and cons, and I feel that we haven’t yet seen it reach its full potential. But as we take this journey, here are some of the tourist traps we’ve seen along the way.

Ultima

Ultima is often forgotten amongst the discussion of The Legend of Zelda’s and Dragon Quests of the world. Released in 1981, it may be the earliest game with a recognizable open world. You’re given a goal and let loose in a cohesive map to traipse across as you deem necessary. There aren’t many caveats you can apply to disclaim its status as a pioneering open-world title.

While its formula may have been an inevitability within the video game landscape, it’s hard to believe how many things it established. It was extraordinarily forward-thinking, and future RPGs owe a lot to it. Of course, Ultima owes a lot to Dungeons and Dragons, but nothing is ever developed in a vacuum.

The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall

In terms of fantasy open-world games, The Elder Scrolls reigns supreme. Say what you want about them, but few series have connected with a large audience as the Elder Scrolls games. While Daggerfall is not the first in the series, it’s the first to have a cohesive open-world. The Elder Scrolls: Arena was a number of randomly generated terrains built around cities that you would fast-travel to. Don’t believe anyone who tells you that you can walk until you cross the border from Skyrim to Morrowind. In Daggerfall, you can walk from Wayrest to Sentinel, you’re just not expected to and it’s ridiculously difficult.

It was also the game that became really playful with the open-world concept. You could travel around and pick up an endless number of side-quests. You could buy a house or a boat. Gain status in various guilds. In a lot of ways, it was deeper than the games that came after, while at the same time being more shallow. It was the start of both the strengths and problems that the series and its many derivatives continue to have.

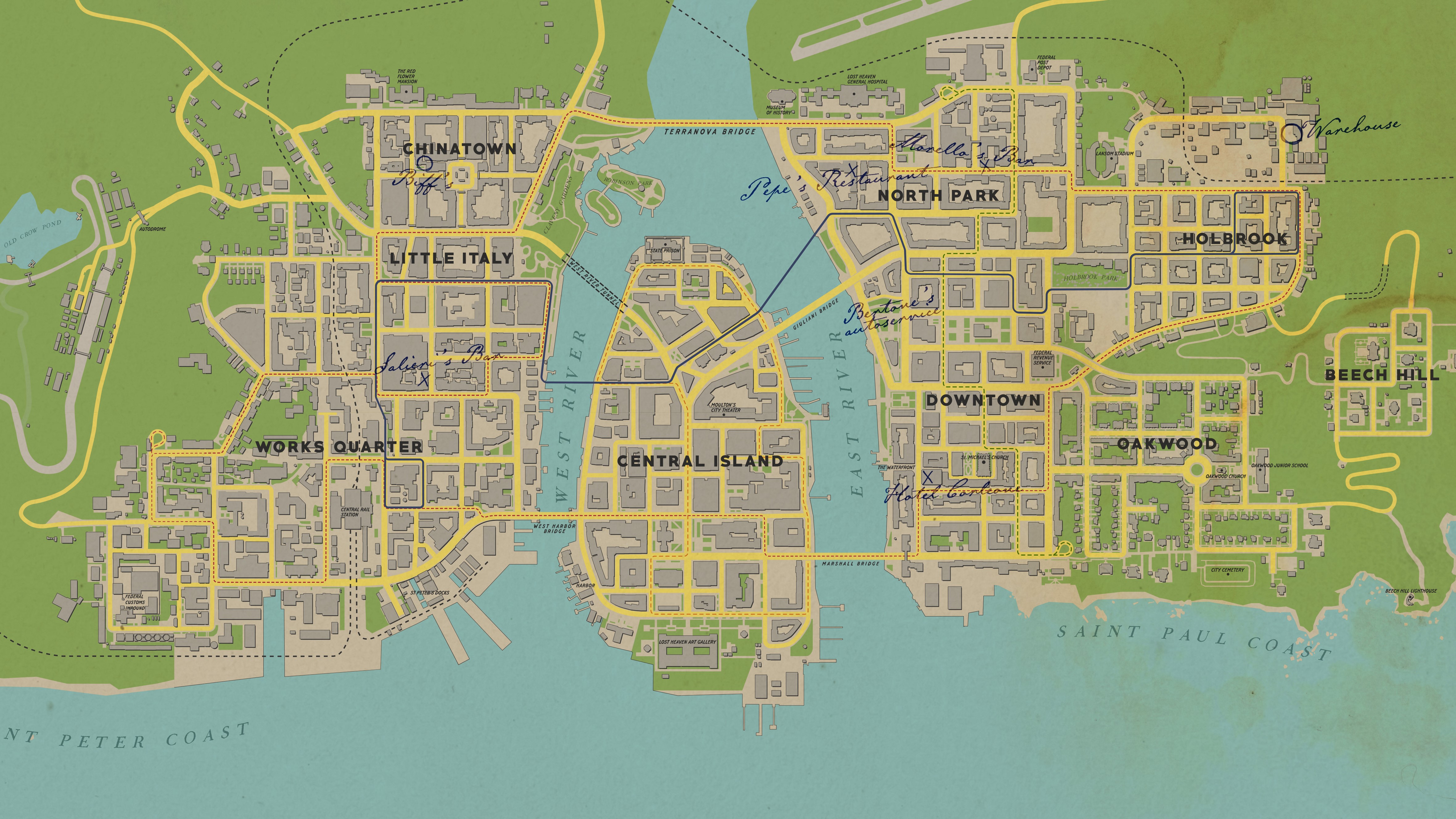

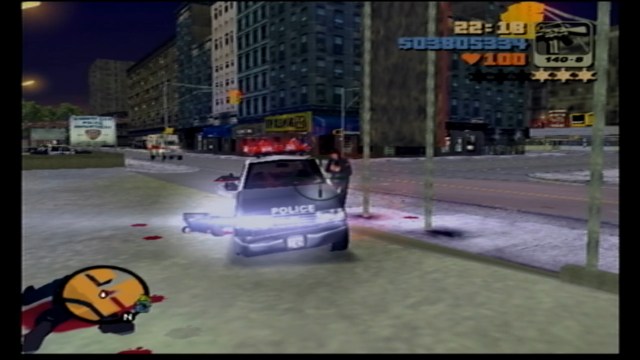

Grand Theft Auto III

Grand Theft Auto III is not the first 3D sandbox city. Not by a long shot. However, it did set a template that similar “crime games” either lived or died by. Lots of side activities, a smattering of secret collectibles, and places to explore. All the imitators that followed would be compared to this title.

The foundation that it set would be built on in differing directions, and one could reasonably say that the Ubisoft formula for open-world would stem from the success of Grand Theft Auto III. It also feels superseded by its direct offspring, but it’s doubtful things would be the same without it.

Assassin’s Creed

Assassin’s Creed is sort of the progenitor to the Ubisoft formula of open-world games. A lot of the facets that go into modern games were set here: the towers that reveal nodes on the map, the endless collections, and the setup of repetitive side-quests to go alongside the story missions.

While many cite Assassin’s Creed as being somewhat disappointing, it did establish a formula that would all but overtake the open-world sub-genre. That might be a disappointment in and of itself.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

You could convincingly claim the original Legend of Zelda as an open-world game. There are no real restrictions on where you can go from the beginning. Afterward, however, the series took cues from Metroid and added barriers that kept you on a critical path to the ending. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild returned the series to its original concept.

After a short prologue, the world is your oyster. With enough preparation, you can go anywhere from the hop. Nothing is strictly restricted. While a lot of rather superficial collecting elements are carried over from other open-world games, much of the artificiality is relieved by its minimalistic approach to direction.