Woke up this morning, got yourself a PS2

Let’s revisit The Sopranos: Road to Respect, which came out last week 15 years ago, on November 7, 2006. Amid the Sopranos resurgence, it’s a happy anniversary to celebrate, but as anyone who has played this game in the last 15 years knows, it’s not very good. It doesn’t even look good.

Instead, all our characters, including James Gandolfini’s Tony Soprano, Michael Imperioli’s Christopher Moltisanti, and our protagonist Joey LaRocca (voiced by Christian Maelen), look like boiled ham hocks, all too circular or too pointy where they shouldn’t be.

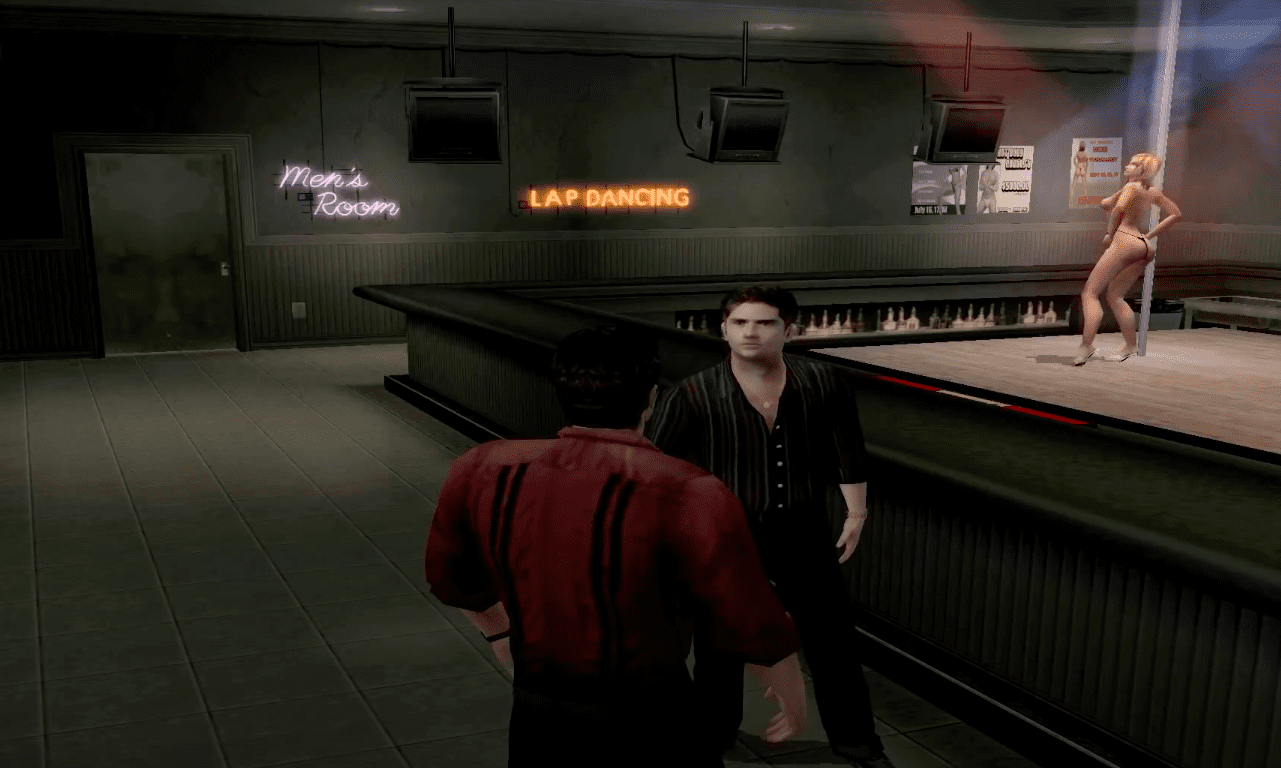

The locations aren’t much better, mostly made up of pale blank walls and boring-til-bloody asphalt. Even our home base, the Bada Bing club, is devoid of any of the show location’s characteristic grime, instead populated by more smooth walls and floors and, yeah, some tables.

In the game, we are Joey, Sal “Big Pussy” Bonpensiero (Vincent Pastore)’s brutish bastard child who never makes it to the TV series. Tony spots us carelessly stealing shit, smashing car windows, and tripping on our face like an embarrassment, outside of Satriale’s Pork Store and decides to bequeath us to Paulie Walnuts (Tony Sirico). Paulie makes us do things like slamming a guy’s head into a urinal until he seems dead and then disappearing his body into the Port of New York waters.

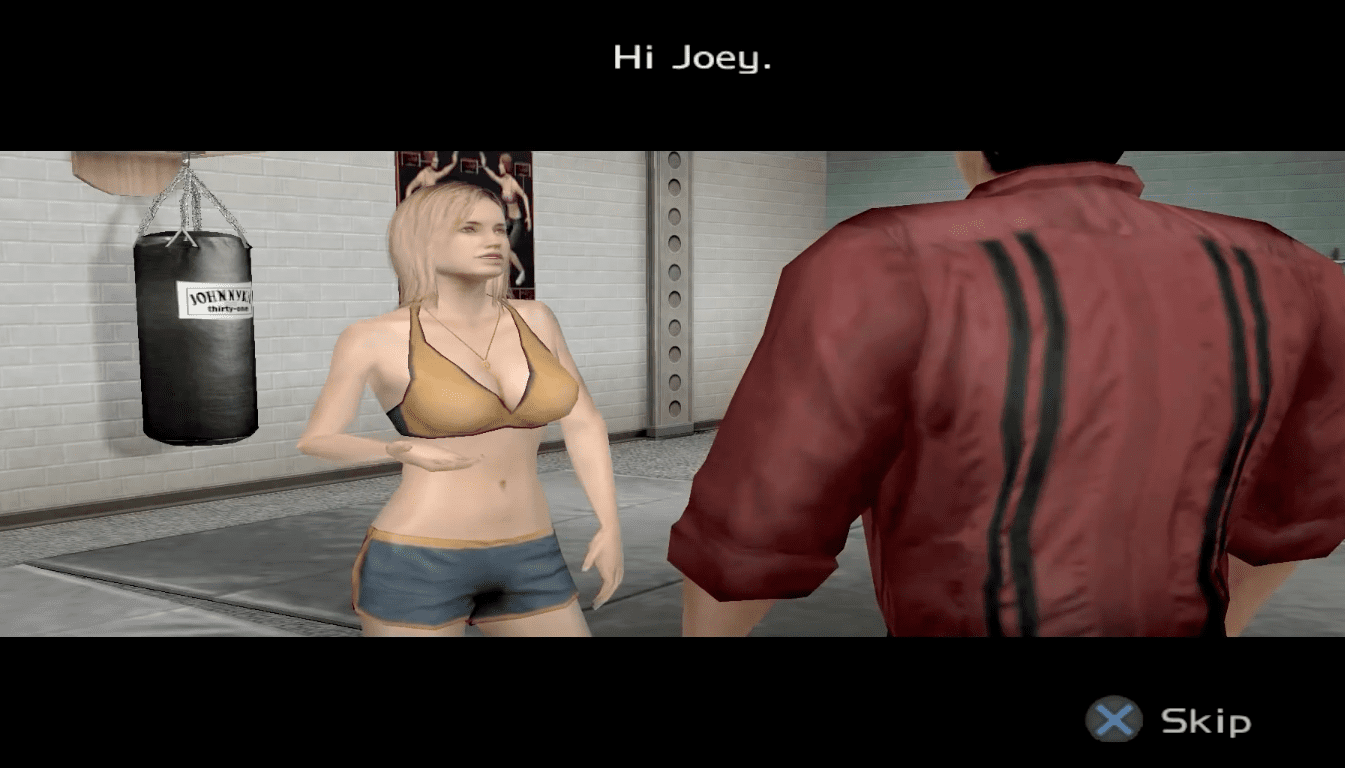

When we look in the mirror, we’re sometimes visited by the ghost of our dad, who disparages and encourages us on our way to joining la famiglia. Eventually, we do join, swearing our blood to the Sopranos, and along the way, we fall in love with Trishelle, who, admittedly, isn’t in the game all that much, but I feel like we should spend some time on since this is a column about women in video games. She is, after all, a woman in a video game.

Like the majority of women characters in Road to Respect, Trishelle is a sex worker, blonde with an hourglass figure. Her voice actress, Monica Keena, lends her a soft New Jersey accent, familiar for Joey, who remembers her from childhood when they stumble into each other at a gym.

After that, Trishelle’s brief screen time consists of a rave gone wrong, getting bombed in her place of work (but then sharing a steamy kiss with Joey when he saves her), and being brutalized by the Sopranos’ rival mob boss after Joey fucks up. So, generally a rough ride for Trishelle, who otherwise seems like a generous, forgiving girl-next-door.

It’s difficult to really compare Road to Respect to the TV series, mostly because Sopranos screenwriter David Chase has said, ahem, “I think [they are] two separate experiences. Playing a game and watching a drama are two completely different things,” but it is worth considering the way Sopranos interacts with women and marginalized characters in any of its mediums. To put it succinctly, that way can be categorized as “poorly,” but it’s hard to expect more from murderers in 2006 whose day-to-day consists of shoving other guys’ heads in urinals. For the Sopranos, women are tools, things you keep around because other people do. They help you out from time to time.

It’s unpleasant to witness here, in its clunky game glory, in the all white, naked women rolling their bodies for glitchy drunks in Bada Bing, but it feels like reality. Like I said, these are bad men. Unfortunately, in this bad game, skinny plot keeps us from trying to understand why they’re so bad to the people around them or how they feel about it.

When Trishelle alludes to being sexually assaulted, we immediately jump to Joey getting revenge, pressing X to mash bones in the ground instead of spending any time on what just happened. Does Joey want revenge because he cares for Trishelle, or does he feel personally disrespected? Why is his instinct violence over consolation? Whereas the show might have spent some time considering motivation, the game tears past it.

It’s fun to remember, 15 years later, but, for women and for everyone, Road to Respect is more novelty than empathy.