Skateboarding is for the birds

[It’s Go Skateboarding Day! And to celebrate, we’re publishing this story about Tony Hawk’s Underground. It was originally meant to run on the game’s thirteenth birthday, but somehow got lost in our CMS. Two years later, here it is. Fuck Eric Sparrow. -Ray]

Tony Hawk’s Underground starts on a depressing note. Its first level is a digital recreation of the Garden State that’s a mess of decrepit row homes and cracked asphalt. Unlike previous Pro Skater levels, New Jersey doesn’t have perfect handrails or embellished takes on iconic skate spots. Instead, there are shitty streets, drained concrete basins, and a bunch of drug dealers.

New Jersey is hardly the best level ever featured in a Tony Hawk game. It is, however, one of the most important. Tony Hawk’s Underground is an underdog story, and underdogs tend to come from dirt. Like Bon Jovi and Bruce, Redman and Ted Leo, the protagonist of Underground rises from Jersey before taking the world by storm.

When Tony Hawk’s Underground was released, it was an anomaly. The Birdman-backed games that came before it treated skateboarding as a silly thing, all crazy combos and mindless replayability. Underground aspired to more by taking the proven gameplay of Pro Skaters past and adapting it to work alongside a fully formed story. It was weird, occasionally stilted, but a genuinely enjoyable journey.

Underground follows the misadventures of a New Jersey skater and his friend Eric Sparrow. The two rise from skate punk scum to legendary professionals. Along the way, they win contests, meet famous skaters, and engage in one of fiction’s most notorious beefs. Even by 2003’s standards, the story was hardly original, but playing through it today, Underground stands out as a game that attempted to portray and humanize skateboarders. It dealt in kickflips sure, but the mischief and filming missions that its characters undertake are touchstones that anyone who spent countless hours pushing around with friends will instantly recognize.

But before Underground really goes anywhere, you still have to get through New Jersey. It’s a far cry from the sleek, architecturally blessed skateboarding mecca of Southern California. The decision to start the first true story-driven Tony Hawk game on the notoriously rough East Coast seems strange at first, but within the context of the classic “hero’s journey” story the game tries to tell, it makes sense. By starting in New Jersey, Underground can emulate the path that countless skaters have embarked on before — and after — its release.

There’s no surefire way to make it big in skateboarding. SoCal rippers tend to come up on a steady diet of perfect handrails and close connections to the industry’s California roots. For those on the East Coast, it’s an entirely different story. Instead of setting sights on Los Angeles, most skaters start by making a beeline towards the Big Apple.

And that’s exactly what happens in Underground. The protagonist and Sparrow escape the seedy NJ streets and hightail it to Manhattan. Though thousands of miles removed from the skateboard industry’s beating heart, New York City has always been a cultural hub of rugged skaters and no-bullshit brands.

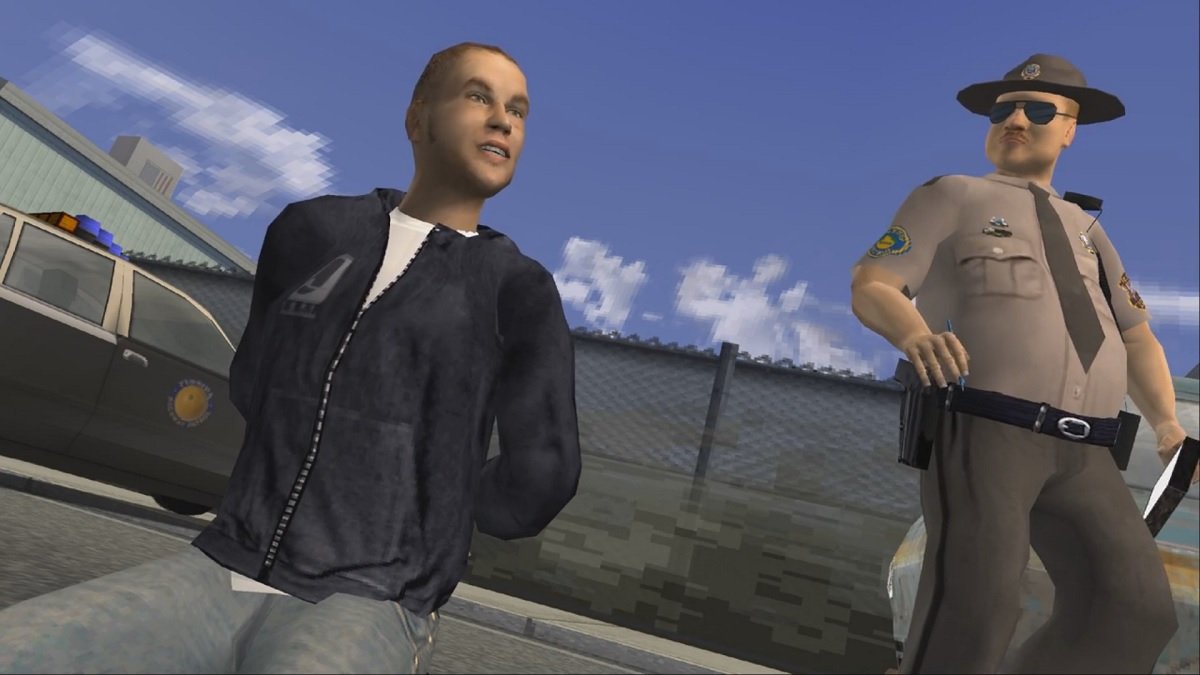

Underground‘s story has players pushing from humble origins in New Jersey to the infamous Brooklyn Banks, and skateboarding’s biggest amateur contest in Tampa, Florida over its first three levels. This works as a means of giving players three distinct environments to skate through while also tracing a path that has a real-world analog to aspiring pros from the East Coast. Underground isn’t just the first game to elevate skateboarding past a nutty, gravity-defying activity, but also the only one in the series that appeals to a “core” skateboarding audience.

Winning Tampa Am is one of the few surefire ways to kickstart a career in skateboarding, and after a stellar performance, the protagonist (and Sparrow) get a golden ticket to sunny California. Again, this follows a similar path that well-known skateboarders have taken — and will continue to — while also sowing the seeds of Sparrow’s heel turn. While Underground has been an interesting, if not gamified version of an underdog’s quest for skateboarding glory up until this point, San Diego and Hawaii mark a turn in the story’s direction.

Once the protagonist has piqued the interest of a real-life skateboard team, it seems as if things are finally coming together. The Jersey-born shredders impress some pros, wow some crowds, and get the opportunity to film a skate video in Hawaii. That’s when things get wild.

Up until the Hawaii trip, Sparrow is a decent, if not a little shady, friend to the protagonist. He’s supportive of the player’s dream of making it big in skating, and always seems to be there when you need him. But, like so many crappy friends, Eric has selfish reasons for sticking with you. While Underground’s protagonist loves skateboarding for skateboarding’s sake — he’s a “soul skater,” if you want to get corny about it — Sparrow sees skating as a means of making millions.

In Hawaii, Sparrow reveals himself as the ultimate snake in the grass. Sparrow, in what is one of gaming’s most memorable acts of villainy, steals footage of the protagonist’s McTwist over the whirring blade of a helicopter. He then edits himself into the video clip — using what’s best described as technical wizardry — and uses the fudged footage to launch his career into the stratosphere.

It’s utterly absurd, of course, but Sparrow’s betrayal stings nonetheless. Up until this point, Underground felt like a send-up to the pure, simple fun that attracts so many people to skateboarding. Eric’s theft takes things down a darker path. The game is no longer about becoming the best skateboarder ever; it’s about getting even with a bitter rival.

Throughout the rest of the game, players spend their time following Eric’s footsteps. Underground’s latter half is about dealing with betrayal and figuring out how to climb up from the bottom once more. Sparrow turns pro, gets a record deal, and generally acts like a rich asshole while the protagonist gets fired from his team and shanghaied in Russia.

While the first handful of Underground levels appealed to a skateboarder’s dreams of making it big, the later portion of the game refocuses — and becomes more relatable in a broad sense — by being about dealing with a bad friend. Who hasn’t had someone screw them over at one point or another? Who hasn’t wanted to get even with a friend who betrayed them? Underground knew exactly what it felt like to be a teenager, and its silly story is just as much about skateboarding as it is about dealing with the anxieties and annoyances that come from being young and awkward, but also old enough to realize that not everything ends perfectly.

Of course, Underground ends on a positive note. Sparrow gets exposed as a fraud after the protagonist assembles a dream team of professional skateboarders and drops the hottest skate video of the year. Players, high off of their video’s success, challenge their former friend to a final challenge where the winner gets the unedited version of the McTwist. You win, obviously, because heroes refuse to quit, and this is a game about being an underdog.

Though its story is hardly the most innovative or groundbreaking thing ever written, it’s a reminder — or maybe a cautionary tale — about the pitfalls of both skating and friendship. Underground wants you to remember that sometimes real life can suck. Your friends might dick you over, and you might get arrested in a foreign country, but skateboarding will always be there for you. It’s not the most profound statement, but at the time of its release, Underground seemed almost prophetic. Hell, at least it’s better than encouraging kids to ollie over homeless people.

Underground’s enduring appeal has just as much to do with its narrative arc as it does with the time it released. By 2003, skateboarding had blown up. What was once an activity reserved almost exclusively for society’s misfits and social outcasts could no longer exist on the fringes. A new generation of skaters had arrived (due in large part to the success of previous Pro Skater games), and Underground had to comment on that. It showed East Coast skaters a path they could aspire to while warning everyone who played it not to trust people named Eric.

Tony Hawk’s Underground came out at the perfect time. It brought the flips and spins of Pro Skater games to new heights by featuring a story that took place on the ground. Games have tackled mature themes and tough subjects, but they’ve never told a story of betrayal quite so well.